Why Network Analysis? A Longitudinal Eating Disorders Case Study

USC Quant Brown Bag

Educational Statistics and Research Methods (ESRM) Program*

University of Arkansas

2025-12-02

About me

Presentation Outline

(35 minutes)

Part I: What is network analysis?

Part II: Why use psychological networks?

Part III: Case Study I — psychological networks of EEG Data

Part IV: Case Study II — longitudinal psychological networks of eating disorders

(15 minutes)

- Part V: Q&A

1 What Is Network Analysis

Network Analysis

Network analysis is a broad area. It has many names in varied fields:

- Graphical Models (Computer Science, Machine Learning)

- Bayesian Network (Computer Science, Educational Measurement)

- Social Network (Sociology, Social psychology)

- Latent Factor Model (Psychology, Education)

- Psychological/Psychometric Network (Psychopathology, Psychology)

All five analysis methods have a network-shaped diagram. Graphical modeling is a more general term that can comprise the other network models.

Networks have varied interpretation

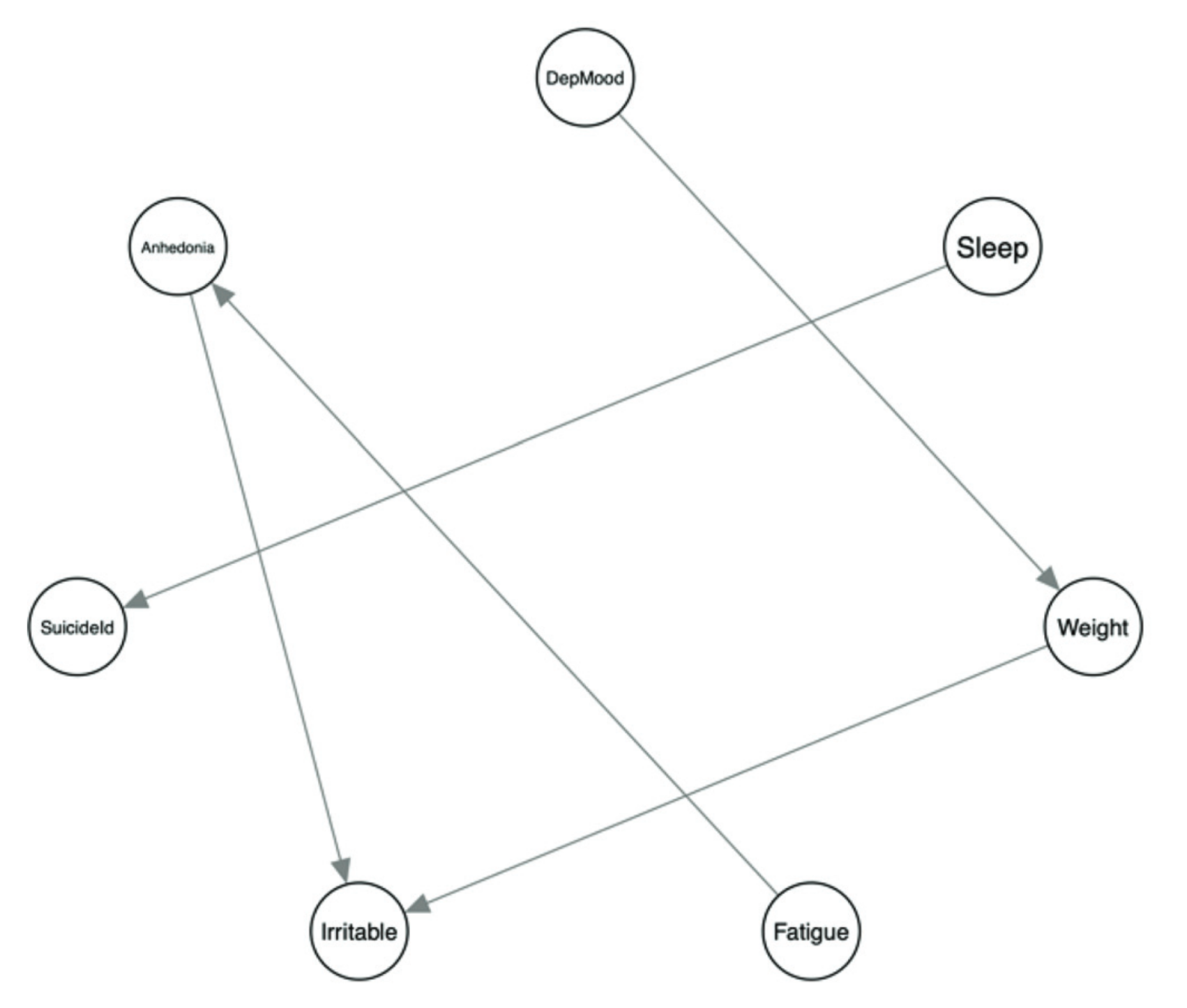

Bayesian networks (BN) or graphical models using Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAG). They aim to derive the causal relations between variables using probabilistic model. The relations are either conditional probabilities (discrete BN) and regression coefficients (Gaussian BN).

Social networks aim to examine the network structure (community, density, or centrality) of social units. The network edges represent the social relationships.

Latent factor model (factor analysis) aims to identify latent variables. The relations represent the regression coefficients.

Psychological networks aim to examine the associations among observed variables (topological structures). The relations represent the partial correlations using Pairwise Markov random fields or the autoregressive parameters using graphical vector autoregression.

Examples of Varied Networks

Psychological Networks and Network Psychometrics

- Network psychometrics is a novel area that represents complex phenomena of measured constructs as sets of elements that interact with each other.

- It is inspired by the mutualism model and research in ecosystem modeling (Kan et al., 2019).

- The mutualism model proposes that basic cognitive abilities directly and positively interact during development.

- Interest in psychological networks has grown as dynamics or reciprocal causation among variables receive more attention.

- For example, individual differences in depression may arise from—and be maintained by—vicious cycles of mutual relationships among symptoms (insomnia -> fatigue -> worrying -> insomnia).

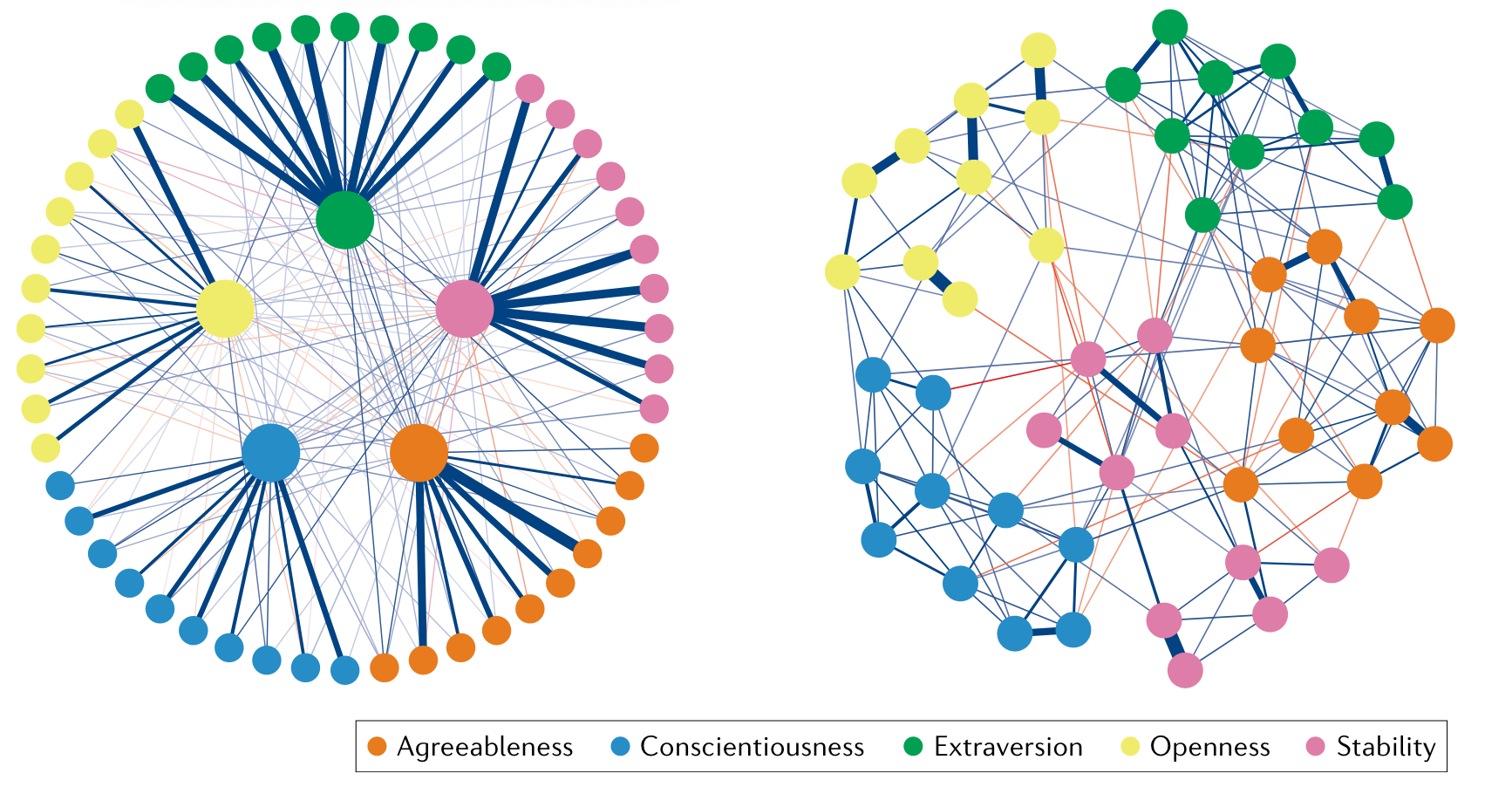

Latent Factor Model vs. Psychological Network Model

Latent factor model (common factor model) assumes that associations between observed features can be explained by one or more common factors (e.g., agreebleness, conscientiousness).

Psychometric networks, however, assume that associations between observed features are the reason for the development of one system. In this view, “personality” is the network itself.

Figure 3: Exploratory factor analysis and psychological network analysis of Big Five personality (Borsboom et al., 2021)

2 Why use psychological networks?

Common factor or Mutualism?

“Openness” dimension:

- Q5. Is original, comes up with new ideas: Disagree (1) to Agree (5) 1

- Q10. Is curious about lots of different things: Disagree (1) to Agree (5)

Does “openness” really exist?

Conditional probability or partial correlation?

BayesNet utilizes the conditional probability P(B|A) to indicate the dependence of child node from parent node. There is assumed direction. The estimation easily become more complex when there are a lot of nodes/variables.

Psychological networks utilizes the partial correlations for cross-sectional data. There is no direction assumption between A and B. Easy to estimate the network structure, but the trade-off is:

- If a BN is the true structure (collider: A -> C <- B), underlying collider structures can introduce spurious negative edges among variables (two symptoms A and B are negatively connected in psychological networks)

Statistical Goals of Psychological Networks

- Explain the pathways of certain psychological phenomena (A <-> B <-> C <-> A).

- Identify the most important problems that need intervention during treatment.

- Examine group differences in interactions among observed features

- Examine network density: a denser network indicates more dynamic interactions (individuals are more likely to be activated).

- Examine clusters/communities of observed features: some symptoms are more likely to co-occur than others.

3 Case Study: A longitudinal EEG network analysis

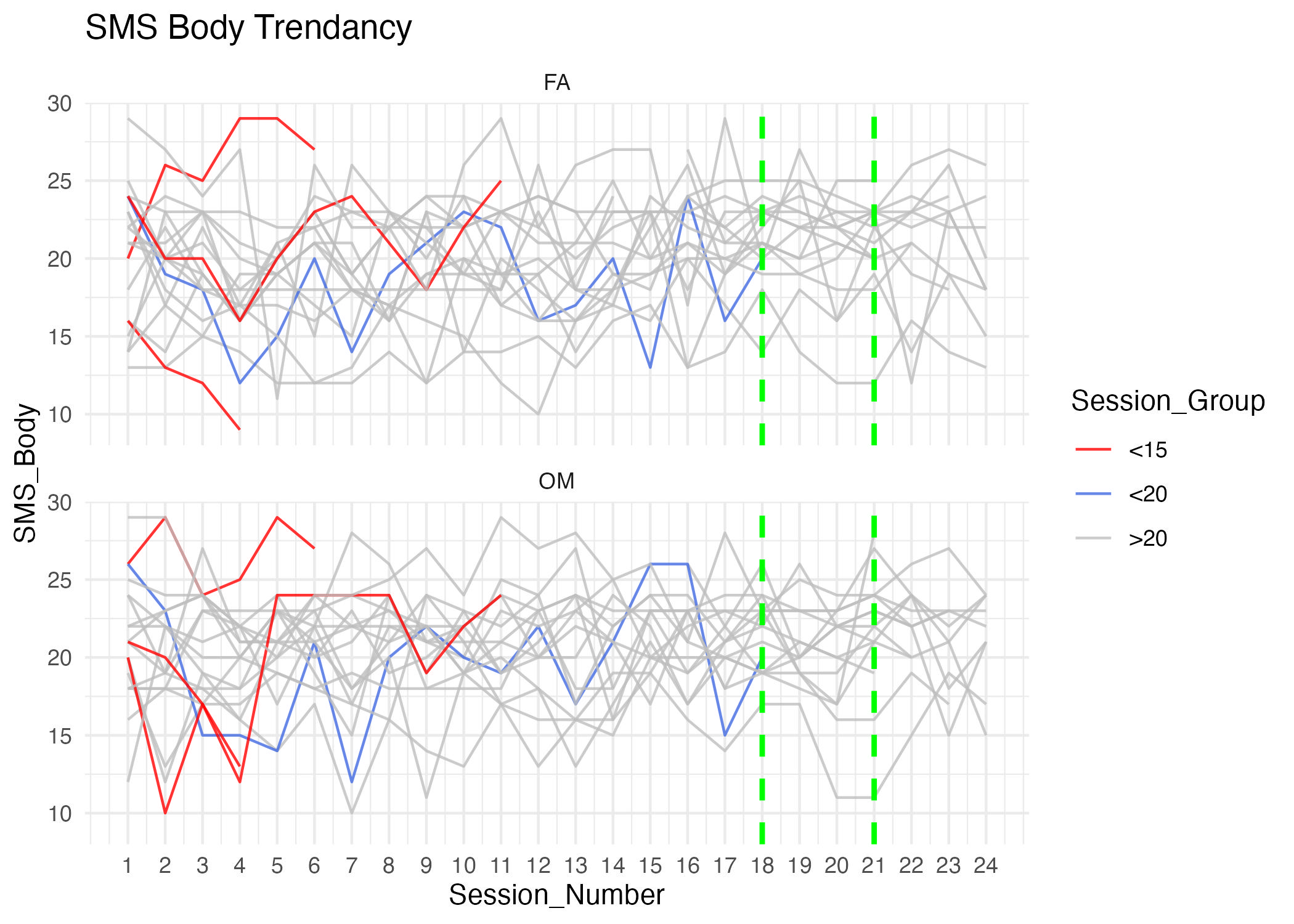

Research background - Intensive Longitudinal Mindfulness (ILM) project

In the area of meditation, there are two types of training:

- focused attention (FA) meditation

- open monitoring (OM) meditation

In recent years, brain activities and cognitive processes engaged during FA and OM mediation are of great research interests.

We believe that the topographical distribution of alpha and theta activity across different scalp regions (e.g., frontal, temporal-central, posterior) may also carry important information for distinguishing the nature of these meditative states

Data

participants completed 8 weeks of FA and OM training

up to 24 EEG-recorded laboratory practice sessions (3 visits per week), during which they completed 20-minutes of standardized audio-guided FA and OM meditation practice (totaling 40 minutes of practice per session).

4 Case Study: Eating Disorder Network

Research background

Eating disorders are serious issues for college students. The eating disorders symptoms are dangerous and co-occur with other psychological issues, which make the intervention more difficult to implement.

Given the complex relationships between eating disorders with other risky behaviors, we need a novel model to untangle those interplay which can help with further intervention.

Q1: Can eating disorders combined with other risky factors be considered a network?

Q2: How do we estimate the longitudinal effect using network model?

Q3: How to compare groups in longitudinal networks

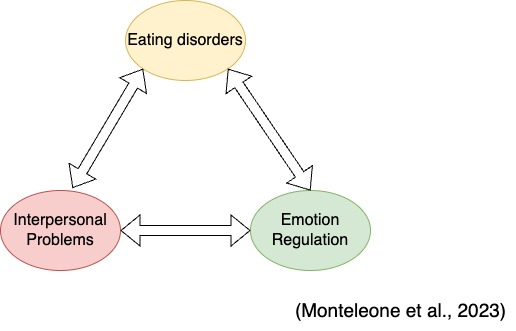

Question 1: Can eating disorders be considered a network?

- Understanding interrelationships among components—emotion regulation, interpersonal problems, and eating disorders—can be conceptualized as a symptom network via theoretical frameworks.

The emotion regulation theory suggests that difficulties in emotion regulation can result in ED behaviors.

Interpersonal psychotherapy theory posits that interpersonal problems may exacerbate ED (Murphy et al., 2012).

Empirical studies consider these three to constitute an “ecosystem” (Ambwani et al., 2014). Emotion regulation and interpersonal functioning exhibit reciprocal effects on the maintenance of ED.

The motivation is to obtain a holistic picture of the eating disorders ecosystem. However, the symptom-level dynamics of eating disorders have not been well investigated.

Question 1 (cont.): Why do eating disorders have a network-like structure?

- Why ED may have a network-like structure

- Some researchers consider the development of ED a longitudinal process (Mallorquí-Bagué et al., 2018).

- Some researchers claimed that the relations between varied risk factors (emotion, interpersonal relations) and ED are complex (i.e., feedback loops).

- Additionally, some highlight that boys and girls exhibit gender differences in the developmental process of ED.

Thus, we consider the interplay between ED, emotional issues, and social issues is a complex ecosystem. Understanding this system in a holistic picture can help with the intervention of ED for clinicians.

Question 2: How do we estimate the longitudinal effecct using network model?

Longitudinal network analysis has been widely applied in psychopathology and is a suitable tool for addressing the problems mentioned in the first general question.

- It considers symptoms related to each other as in a symptom network.

- It allows us to identify the most important symptoms (disordered behaviors) in this complex network.

- It can estimate the temporal effects of one symptom on others while controlling for other variables.

Question 2 (cont.): How do we estimate the longitudinal effecct using network model?

We estimated network parameters using the graphical vector autoregression (GVAR; Epskamp, 2020; Wild et al., 2010) algorithm.

We estimate three types of network structures:

Temporal network (temporal effects)

Contemporaneous network (within-person effects controlling for temporal effects)

Between-individual network (individual differences)

Question 3: How to compare groups in longitudinal networks

In network analysis, groups can be compared from three aspects:

Network structure (e.g., some nodes connected in group A but not in group B).

Node-level measures: node centrality (importance) or node bridging strength (e.g., some nodes may be more connected to other communities).

Network edge weights (e.g., node 1 and node 2 may have a strong relationship in group A but a weaker relationship in group B).

Things to Consider

Which variables (nodes) should be included in the network?

- Items?

- Subscale scores?

- Latent factor scores?

- Mixed

There are no clear rules for node types; it depends on the theoretical model.

- Are different networks comparable?

If the network of sample A differs from the network of sample B in terms of network structures or centrality measures, are these merely quantitative differences in parameter estimates, or are they measuring different constructs?

Research Questions

- Are there gender differences in the network characteristics of longitudinal networks?

- Are there gender differences in the network structures of eating disorder longitudinal networks?

- Are there gender differences in node centrality and bridge strength of longitudinal networks?

Data

Four waves of data were collected over 18 months.

For each wave, demographic information and self-reports on three questionnaires (emotion regulation, interpersonal problems, and eating disorders) were collected from 1,652 high school students in China.

After data cleaning, N = 1,540 remained, including 53.9% girls and 46.1% boys.

Ages ranged from 11 to 17 years, with a mean of 15.2 years.

Measures

For network analysis, we used subscales and items as nodes.

- Emotion regulation: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-18). Six subscales measure different aspects of emotion dysregulation: Awareness, Clarity, Goals, Non-acceptance, Impulse, Strategies.

- Interpersonal problems: Inventory of Interpersonal Problems—Short Circumplex (IIP-SC). Eight subscales measure varied aspects of interpersonal problems (e.g., domineering, cold, avoidant).

- Eating disorders: 12-item short form of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-QS). Twelve items measure different disordered eating behaviors.

We have 26 nodes in the initial networks.

Data Analysis

1. Node (item) selection

For emotion regulation and interpersonal problem questionnaires, 14 subscales were selected because their constructs have been well examined and are theory-driven.

For eating disorders, we wanted to ensure each item represented a unique problem. Thus, we used the goldbricker algorithm to drop overlapping (duplicated) symptoms, resulting in 8 items included in the analyzed network.

We have 22 nodes in further network analysis.

2. Network estimation

Multi-group GVAR was applied to estimate boys’ and girls’ temporal, contemporaneous, and between-subject networks.

Furthermore, we pruned the networks and identified the most important nodes and edges using the

prunefunction in thepsychonetricspackage in R.

Data Analysis (Cont.)

3. Overall network evaluation

- Network stability was measured by correlation stability (CS) coefficients (Epskamp et al., 2018), which estimate the accuracy of network structure and centrality measures using bootstrapping.

4. Test group differences

Use the likelihood ratio test (LRT) to examine network structure differences by gender.

Model H0: all edge weights constrained to be equal.

Model H1: all edge weights freely estimated.

Calculate the likelihood ratio between H0 and H1 and perform a significance test.

Examine gender differences in node centrality and bridge strength.

Compare estimated node centrality and bridge strength by gender.

Accuracy: test the accuracy of node centrality differences using bootstrap sampling.

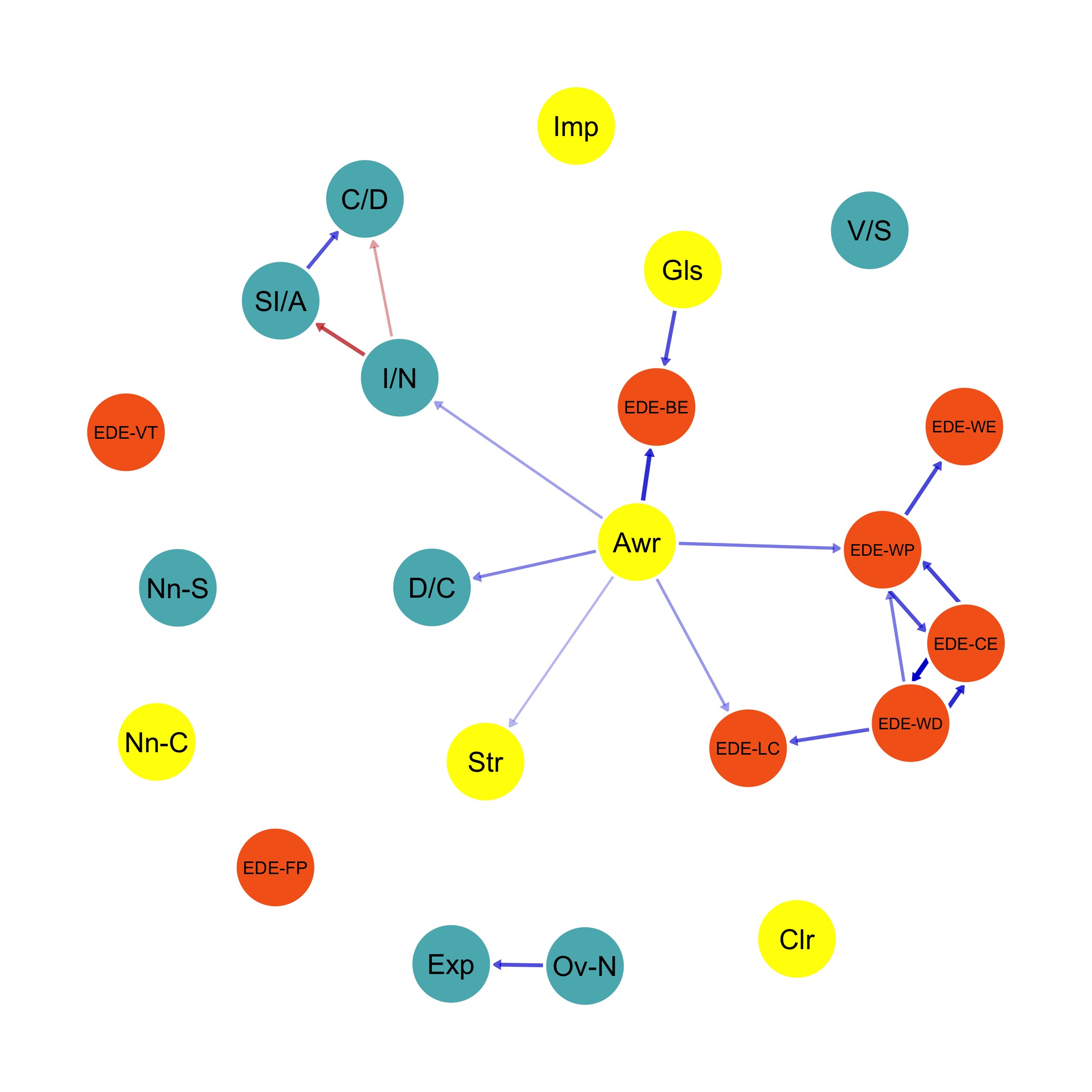

Results

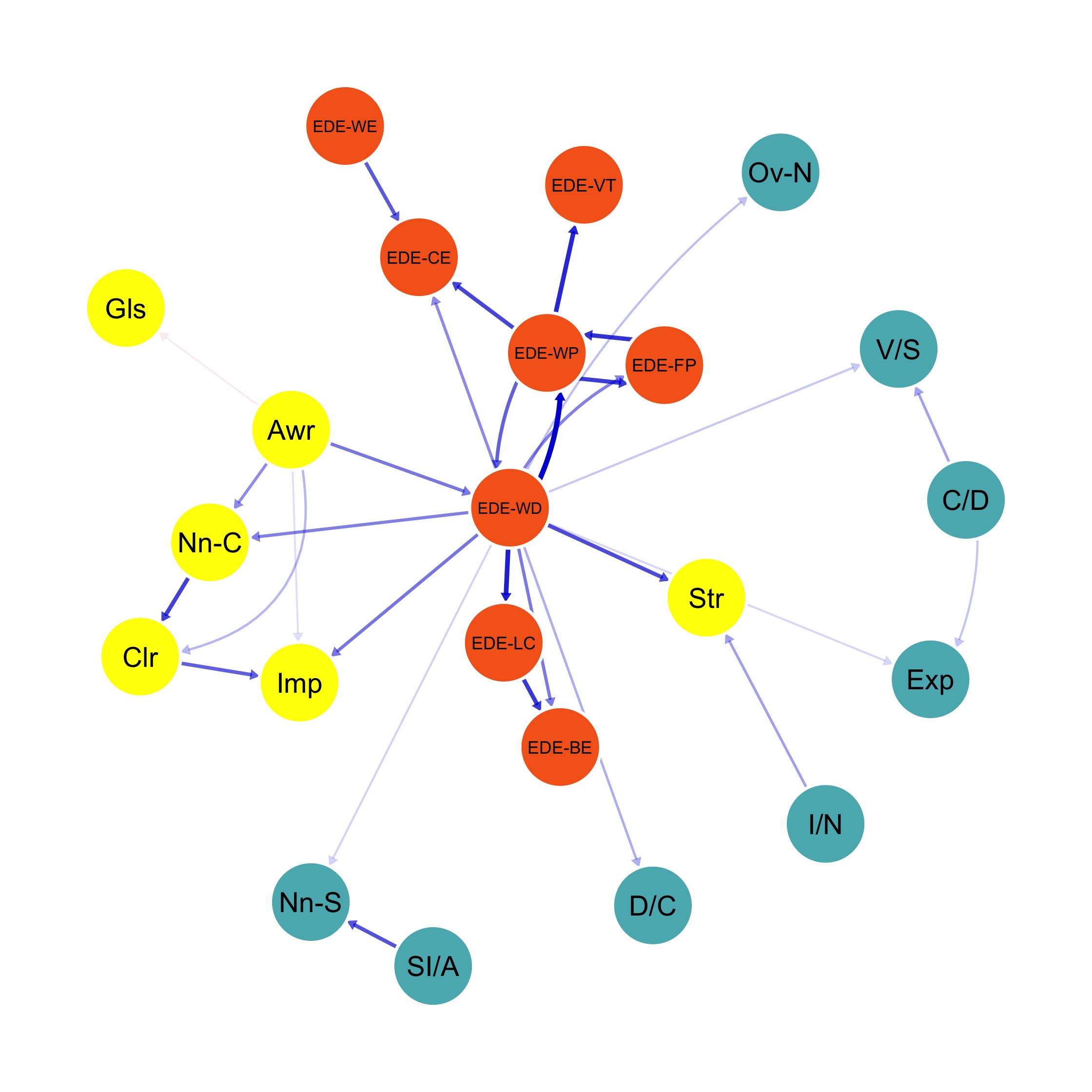

Temporal Network Structure (left: boys; right: girls)

Overall Network Stability

Correlation Stability

- The multigroup network stability statistics were acceptable for contemporaneous and between-subject networks according to the criterion of CS coefficients above 0.7.

- Network models also have SEM model fit indices like RMSEA, TLI, CTI etc.

- The temporal network was less stable, with CS coefficients ranging from 0.51 to 0.56. Less stable indicates higher residual errors overall.

Group Differences — Temporal Network

Boys

- Sparsity: 8.06% of non-zero edges (temporal)

- Strength: Mean (SD) of edge weights is 0.127 (0.094).

- Node weight/shape preoccupation (EDE-WP) exhibited the highest InStrength

- Node weight/shape dissatisfaction (EDE-WD) exhibited the highest OutStrength

- Node Awareness (Awr) exhibited the highest bridge strength

Girls

- Sparsity: 10.60% of non-zero edges (temporal)

- Strength: Mean (SD) of edge weights is 0.128 (0.102).

- Node weight/shape preoccupation (EDE-WP) exhibited the highest InStrength

- Node weight/shape dissatisfaction (EDE-WD) exhibited the highest OutStrength

- Node weight/shape dissatisfaction (EDE-WD) exhibited the highest bridge strength

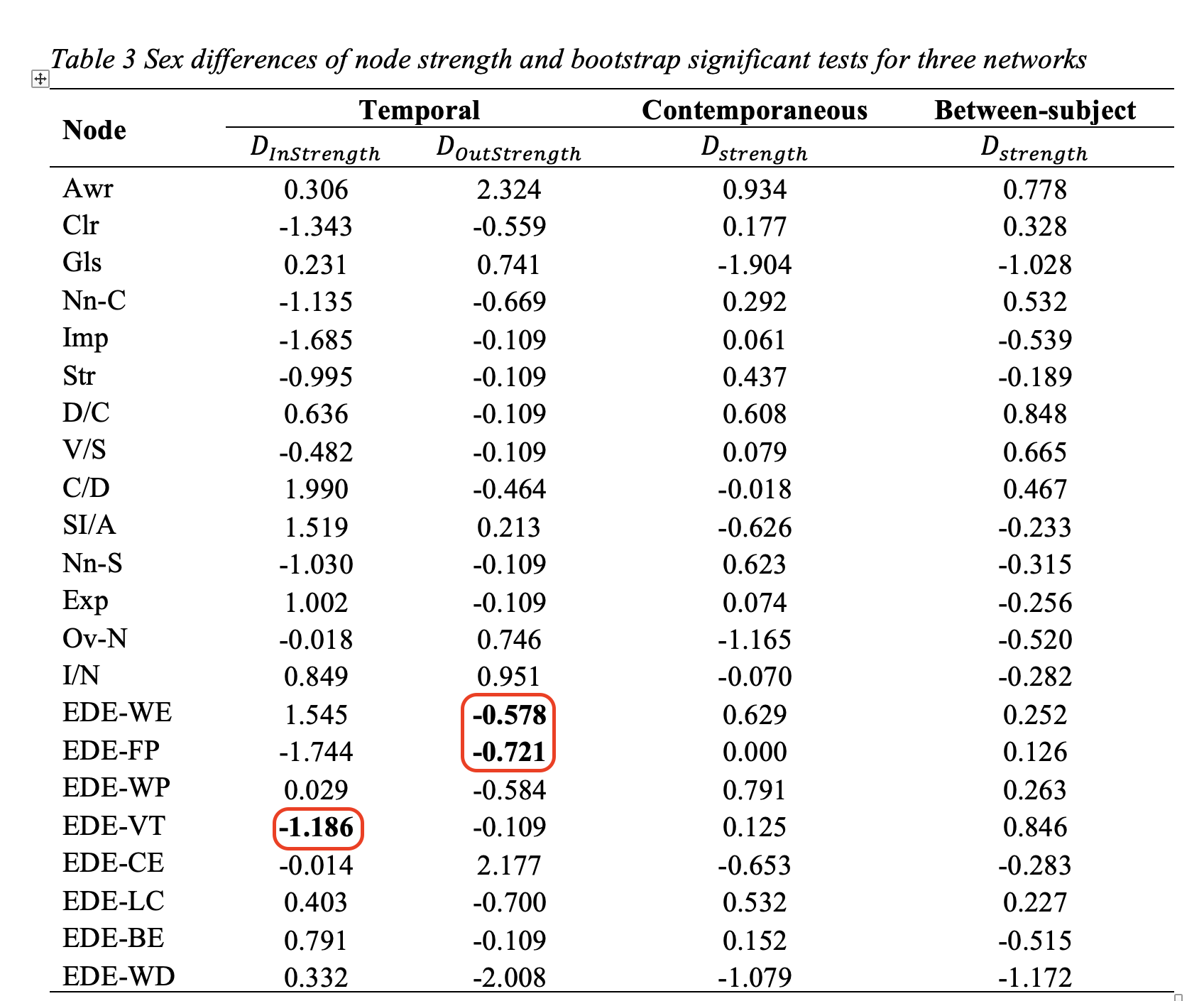

Checking which node’s importance is different

Are the node differences due to sampling error? We used bootstrapping to test this:

- Long periods without eating (EDE-WE) and Food preoccupation (EDE-FP) have significant gender differences in node out-strength.

- Weight/shape control by vomiting or taking laxatives (EDE-VT) has significant gender differences in node in-strength.

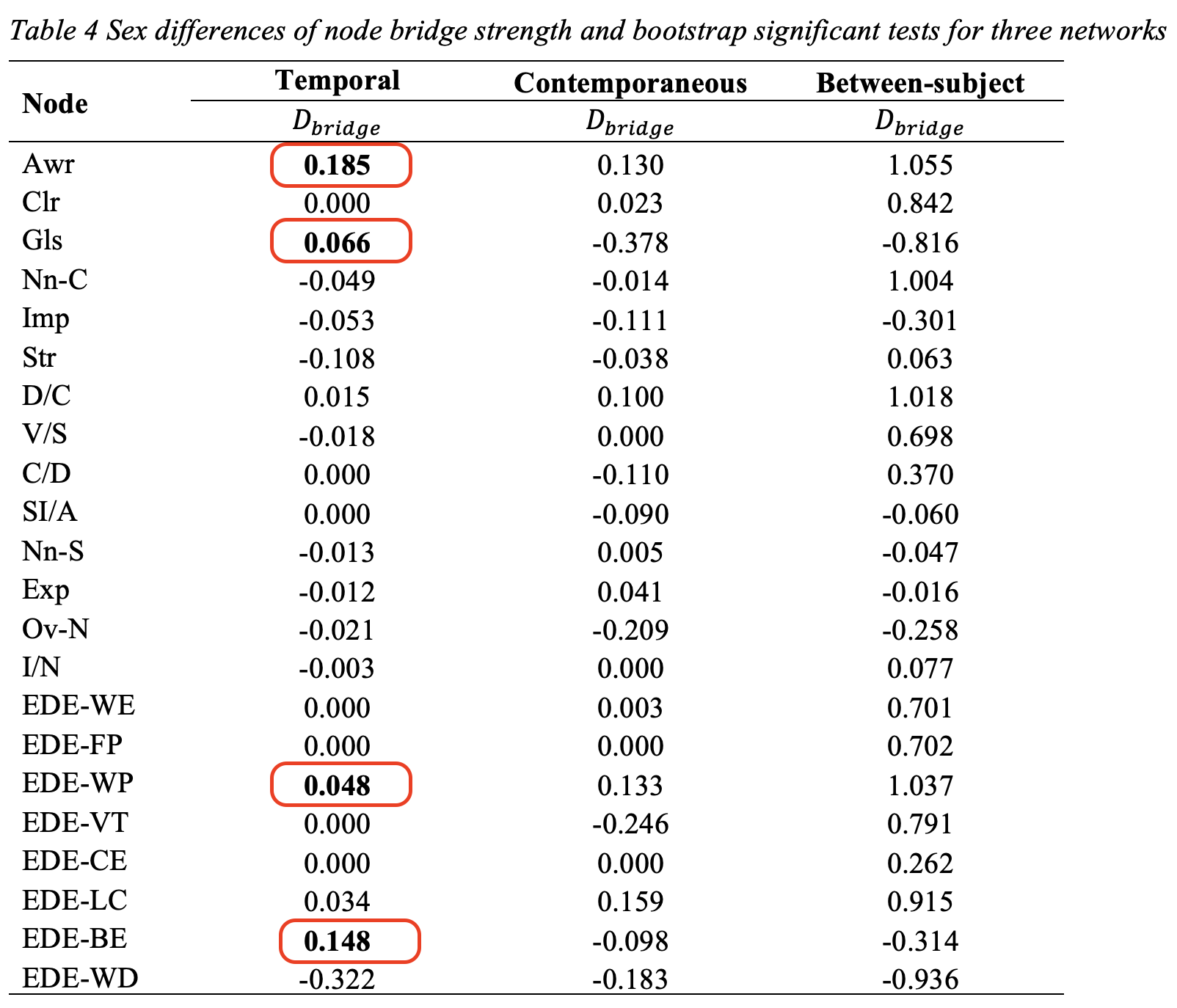

Checking which node’s bridge strength is difference

Are the node differences due to sampling error? We used bootstrapping to test this:

- Awareness (Awr) and Goals (Gls) have higher bridge strength in boys than girls.

- Weight/shape preoccupation (EDE-WP) and Binge eating episode (EDE-BE) have higher bridge strength in boys than girls.

Target nodes for intervention on comorbidity.

Discussion: Group Commonalities

Edge weight strengths of the temporal network are similar for boys and girls, suggesting symptoms have similar impacts on other symptoms.

Emotion dysregulation has interconnections with eating disorders and interpersonal problems.

Disordered eating behaviors also closely relate to each other within the eating disorder community. One disordered eating problem is likely to activate other problems.

For both groups, nodes related to the overvaluation of weight/shape (preoccupation or dissatisfaction) are the most influential factors in ED networks, implying these symptoms should be a main focus for eating disorder interventions.

Discussion: Group Differences

- Network structures of boys and girls are significantly different in terms of the likelihood ratio test (LRT).

- Nodes in the girls’ network are more densely related than in the boys’ network, suggesting a higher likelihood of comorbidity for girls.

- A lack of emotional awareness is a potential maintenance factor for boys, which is a novel finding.

- Girls’ weight/shape dissatisfaction has stronger impacts on emotion issues and interpersonal issues than boys.

- Girls’ weight/shape dissatisfaction is likely bridge eating disorders together with other emotional or social issues.

Further Directions

There are still some challenges to examine group differences in the longitudinal network framework:

Validity

- “Weight/shape dissatifaction” means differently to boys and girls. In other words, boys and girls have different body images.

Interential statistics

- More simulation studies to validate the LRT method for examining group differences in longitudinal network structure.

Interpretation

Groups may differ in network density and average edge weights. What this means in applied research needs further investigation.

Groups may differ in the most important nodes and also in less important nodes. What does that mean, and how should we interpret it?

Are groups’ edge weights comparable? For example, if the partial correlation between node A and node B differs by group, how should we interpret that?

5 Q&A

Thank you.

Let me know if you have any questions.

You can also contact me via jzhang@uark.edu

Reference