Network and AI-Driven Approaches in Psychometrics and Behavioral Science: Concepts and Empirical Case Studies

Department of Social and Behavioural Science, CityU, HK

Educational Statistics and Research Methods (ESRM) Program*

University of Arkansas

2025-12-18

About me

Research Path

Presentation Outline

30 minutes

Part I: Foundations of network analysis

- What is network analysis

- Why use psychological networks

- Latent factor models vs. Network analysis

Part II: Empirical applications

- EEG-based networks

- Eating disorder symptom networks

Part III: Emerging directions: AI-augmented psychometric research

15 minutes

- Part IV: Q&A

1 What Is Network Analysis

Network Analysis in General

Network analysis is a broad area. It has many names in varied fields:

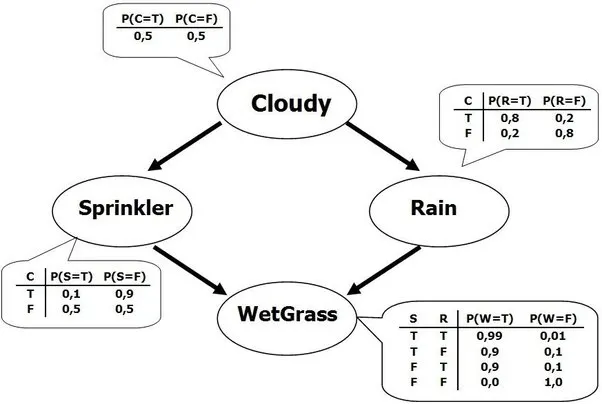

Graphical Model (Computer Science, Machine Learning)

- History: Statistical physics, such as large system of particles (Lauritzen, 1996)

- Bayesian Network (Computer Science, Educational Measurement)

- Social Network (Sociology, Social psychology)

- Latent Factor Model or Structural Equation Model (Psychology, Education)

- Psychological Network Analysis (Psychopathology, Psychology)

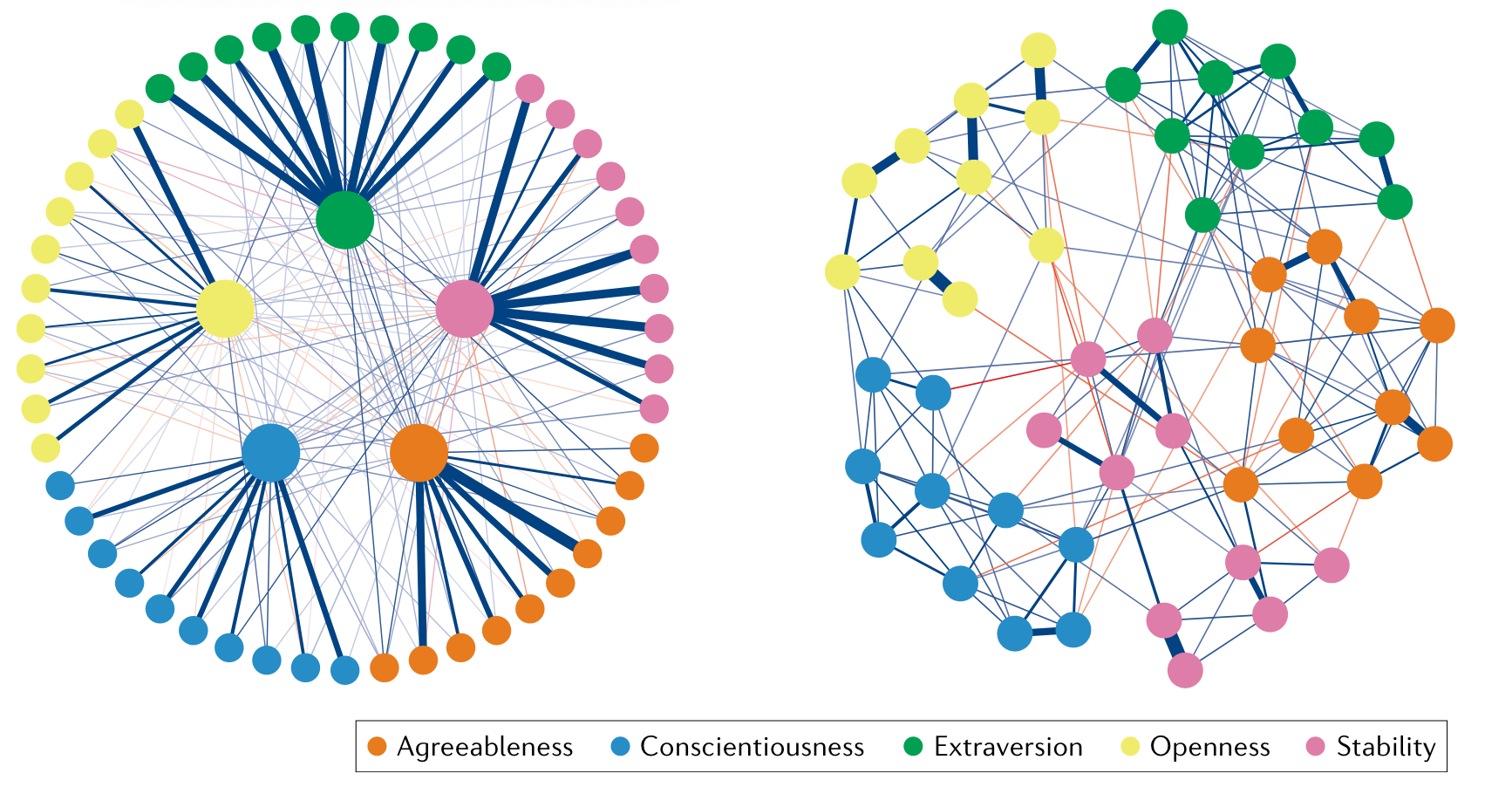

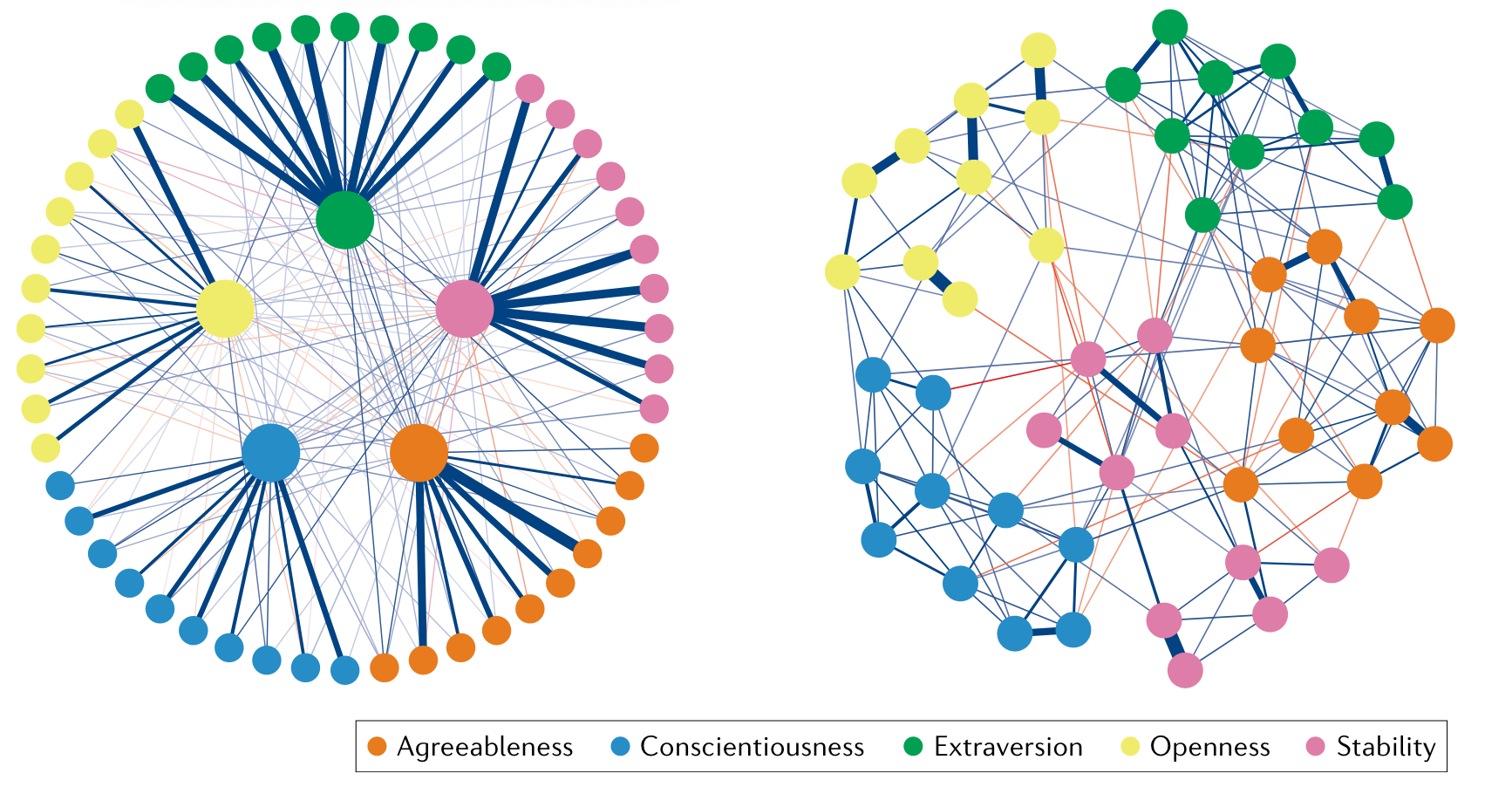

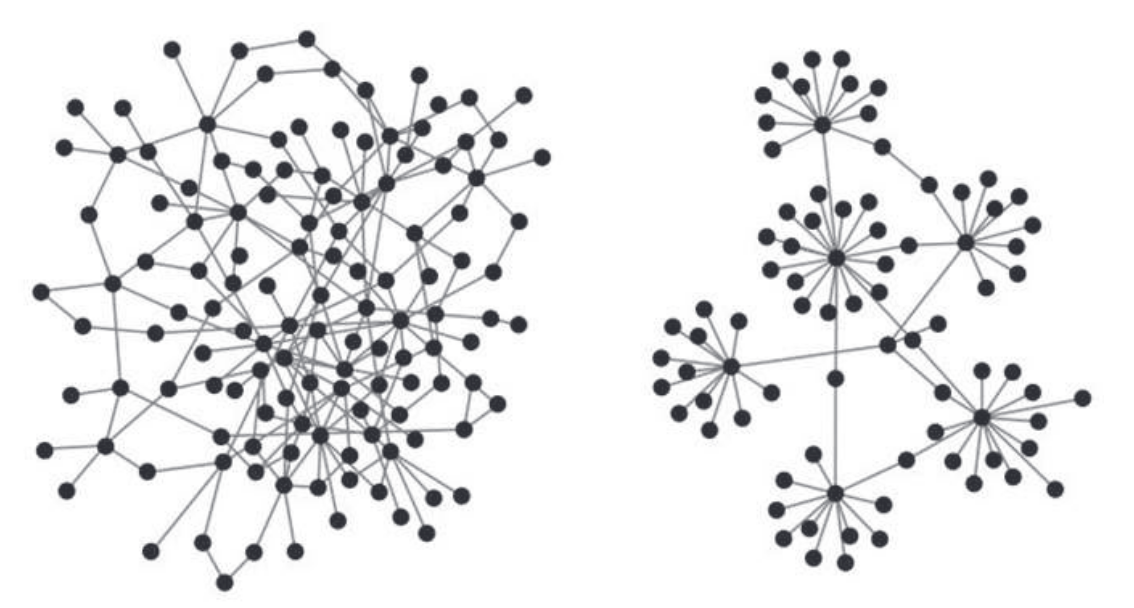

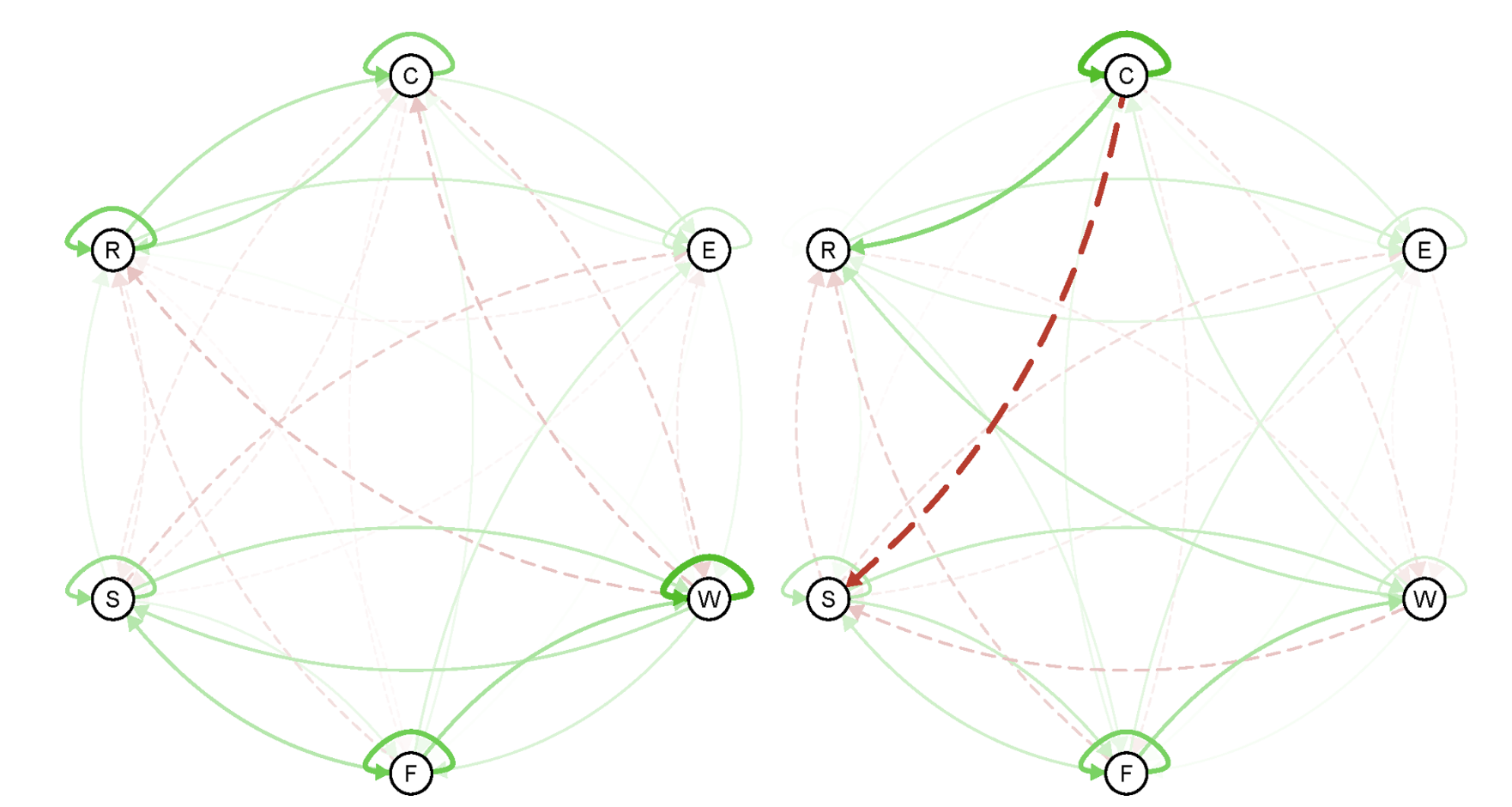

Figure 2: Exploratory factor analysis and psychological network analysis of Big Five personality (Borsboom et al., 2021)

Commonality: Key Components in the network

All network models share common structural elements:

Nodes (vertices): Random variables, individuals, or units of analysis

Edges (links): Relationships or connections between nodes

- Directed vs. Undirected

- Weighted vs. Unweighted

Adjacency matrix: Mathematical representation of the network

- Rows and columns represent nodes

- Entries indicate presence/strength of edges

Paths and Cycles: Sequences of connected nodes

Uniqueness: Statistical dependence & Purpose

Different network models represent distinct types of statistical dependence:

Bayesian networks (DAG): Conditional dependence P(X | Parents)

Social networks: Observed social relationships among social units

Latent factor models: Marginal dependence via common latent causes

- Observed variables are conditionally independent given latent factors

Psychological networks: Conditional dependence given all other variables

- Partial correlations (cross-sectional) or lagged effects (temporal)

Psychological Networks and Network Psychometrics

Network psychometrics is a novel psychometric area that represents complex phenomena of measured constructs as sets of elements that interact with each other (Isvoranu et al., 2022).

It is inspired by the mutualism model and research in ecosystem modeling (Kan et al., 2019).

- The mutualism model proposes that basic cognitive abilities directly and positively interact during development.

In recent years, interest in psychological networks as dynamics or reciprocal causation among variables receive more attention.

2 Why use psychological networks?

Latent Factor Model VS. Psychological Network Model

Latent factor model (common factor model) assumes that associations between observed features can be explained by one or more common factors (e.g., agreebleness, conscientiousness).

Psychometric networks, however, assume that associations between observed features are the reason for the development of one system. In this view, “personality” is the network itself.

Exploratory factor analysis and psychological network analysis of Big Five personality (Borsboom et al., 2021)

Common factor or Mutualism?

“Openness” dimension:

- Q5 (Creativity). … comes up with new ideas: Disagree (1) to Agree (5) 1

- Q10 (Curiosity). … curious about lots of different things: Disagree (1) to Agree (5)

Does “openness” really exist?

Research aims: Density, Centrality, Pathways, and Group Differences

Aim 1. Network Density

Assess overall connectivity and sparsity (system activation likelihood)

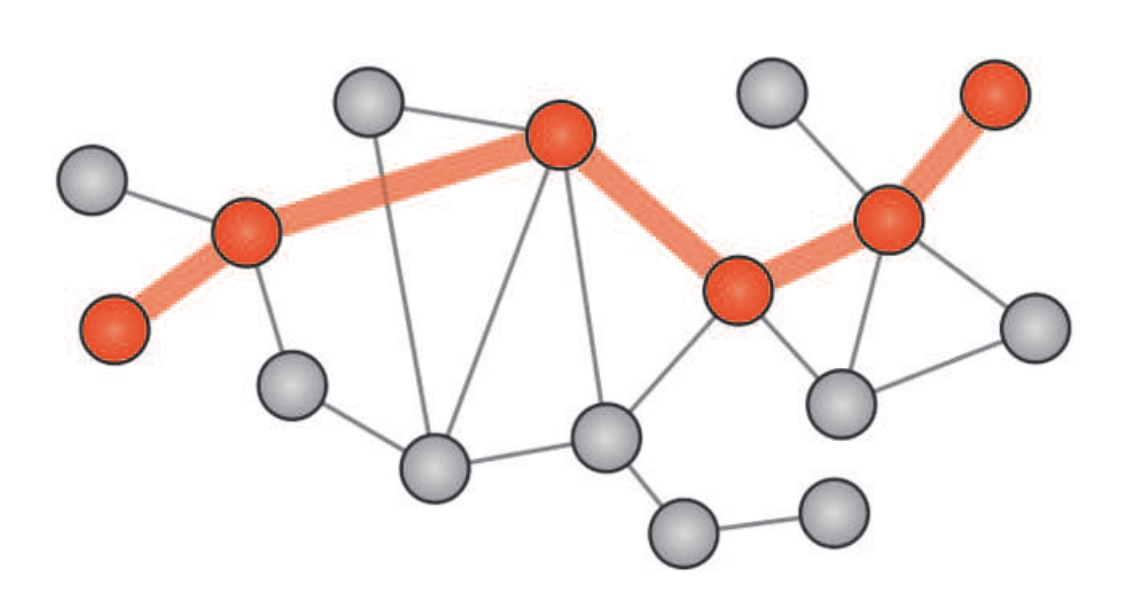

Aim 2. Identify Pathways

Map symptom interactions and feedback loops (A ↔︎ B ↔︎ C ↔︎ A)

Aim 3. Intervention Targets

Identify the most central/influential nodes for treatment

Aim 4. Group Differences

Compare network structures across populations

These analytical goals help bridge theory and practice, guiding both our understanding of psychological phenomena and clinical decision-making.

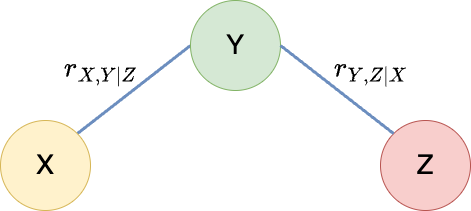

Data types: Cross-sectional vs. Longitudinal network

Cross-sectional network

- Data: Multivariate cross-section data

- Model: Gaussian graphical model (GGM)

- Dependence: The variables depend on other variables at the same time

- Edge Statistics: Partial Correlation (\(r\))

- Methodology: Correlation analysis

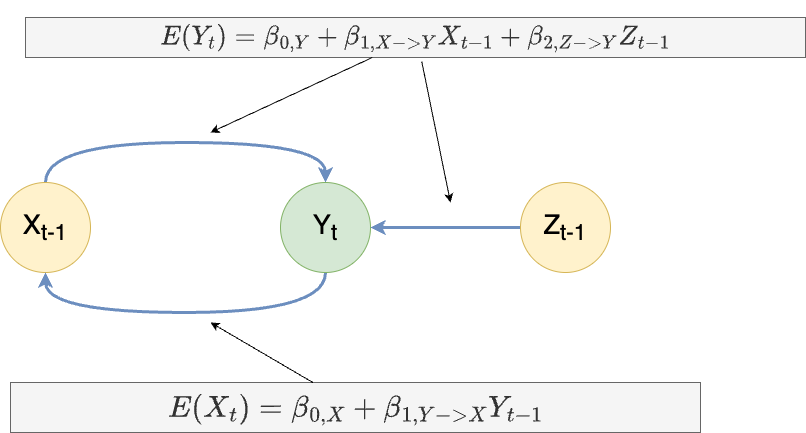

Longitudinal network (today’s focus)

- Data: Multivariate time-seires data

- Model: Graphical vector autoregressive (VAR) model

- Dependence: The values of the variables at time \(t\) depend linearly on the values at time \(t -1\)

- Edge Statistics: Lag-1 regression coefficient (\(\beta\))

- Methodology: Granger-causality

3 Case Study 1: A longitudinal Electroencephalography (EEG) network analysis

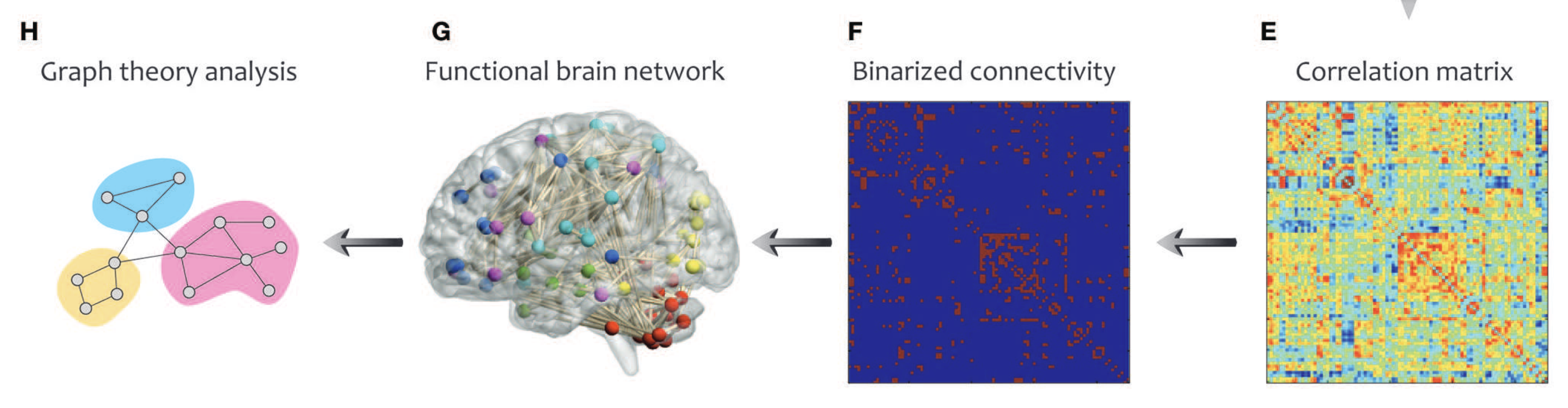

Brain Activity Networks

The human brain is one of the most complex networks in the world.

– Farahani et al. (2019)

Research background

The team utilize a meditation training called Focused Attention (FA) meditation to improve participants’ meditation quality.

Key question:

- What is the relationship between brain activities and participants’ meditation outcomes.

Why use network analysis for EEG data?

- Functional connectivity: Brain regions interact and coordinate during cognitive processes

- Brain dynamics: Alpha and theta rhythms reflect neural communication across brain regions

- Topographical patterns: Multiple brain regions (frontal or posterior) form interconnected systems

- Temporal changes: Allow us to track Longitudinal effects which indicates brain network activities developing with meditation training

Data

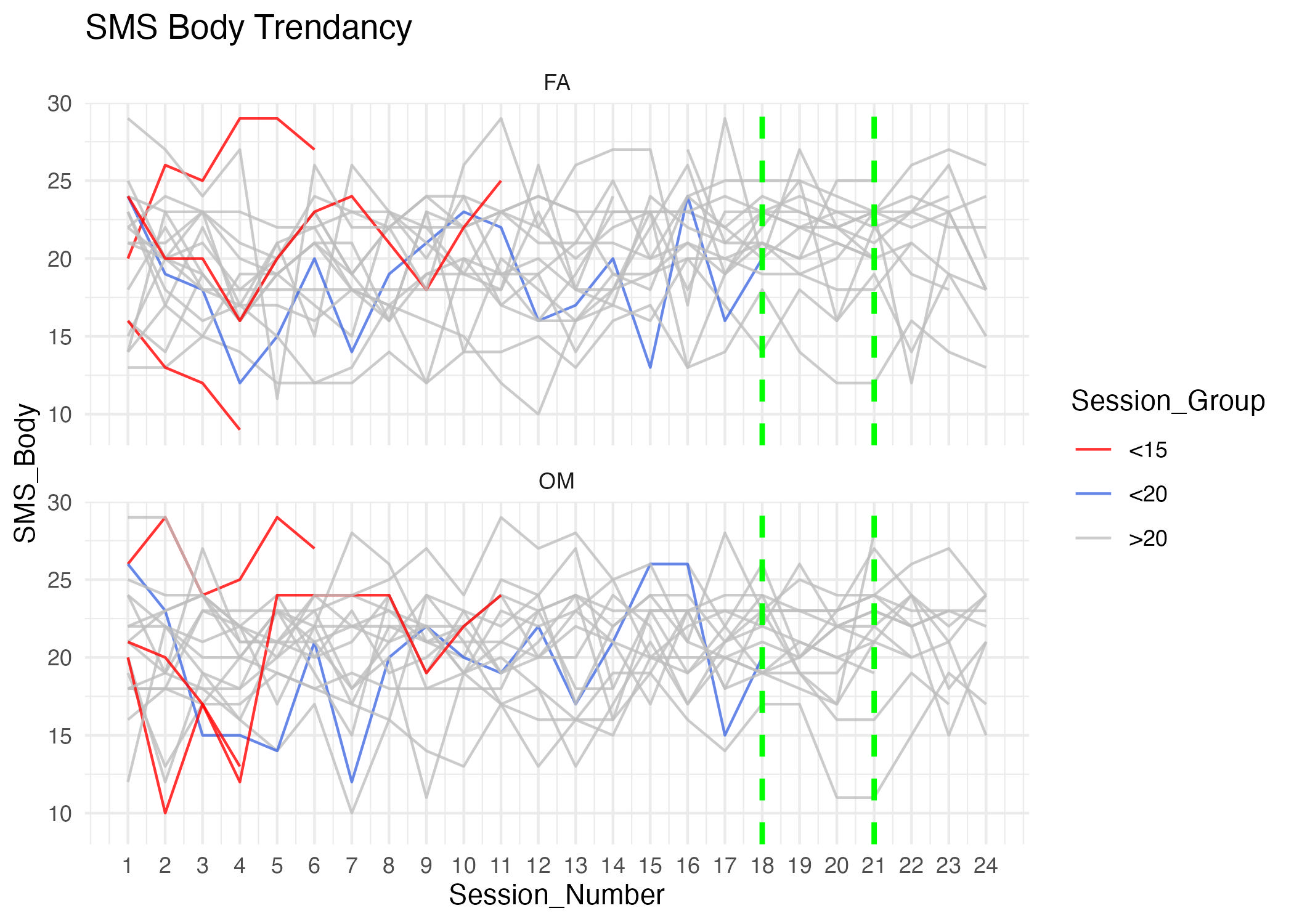

Sample: 19 participants completed 8 weeks of FA training with 3 visits per week, resulting in 24 sessions.

Training: in each session, they completed 20-minutes of standardized audio-guided Focus Attention meditation practice. EEG data was collected

Measure: Self-reported State Mindfulness Scale (SMS_Mind) and body (SMS_Body)

Nodes

2 State Mindfulness Nodes

SMS_Mind: the subjective quality of mindfulness of mind (e.g., thoughts, emotions, mental acuity)

SMS_Body: the subjective quality of mindfulness of body (e.g., physical and bodily sensations)

6 EEG Nodes: Alpha (8-12 Hz; relaxed wakefulness) and Theta (4-8 Hz; light sleep) power separated across respective frontal, temporal-central, and posterior regions

- frontal alpha

- frontal theta

- temporal-central alpha

- temporal-central theta

- posterior alpha

- posterior theta

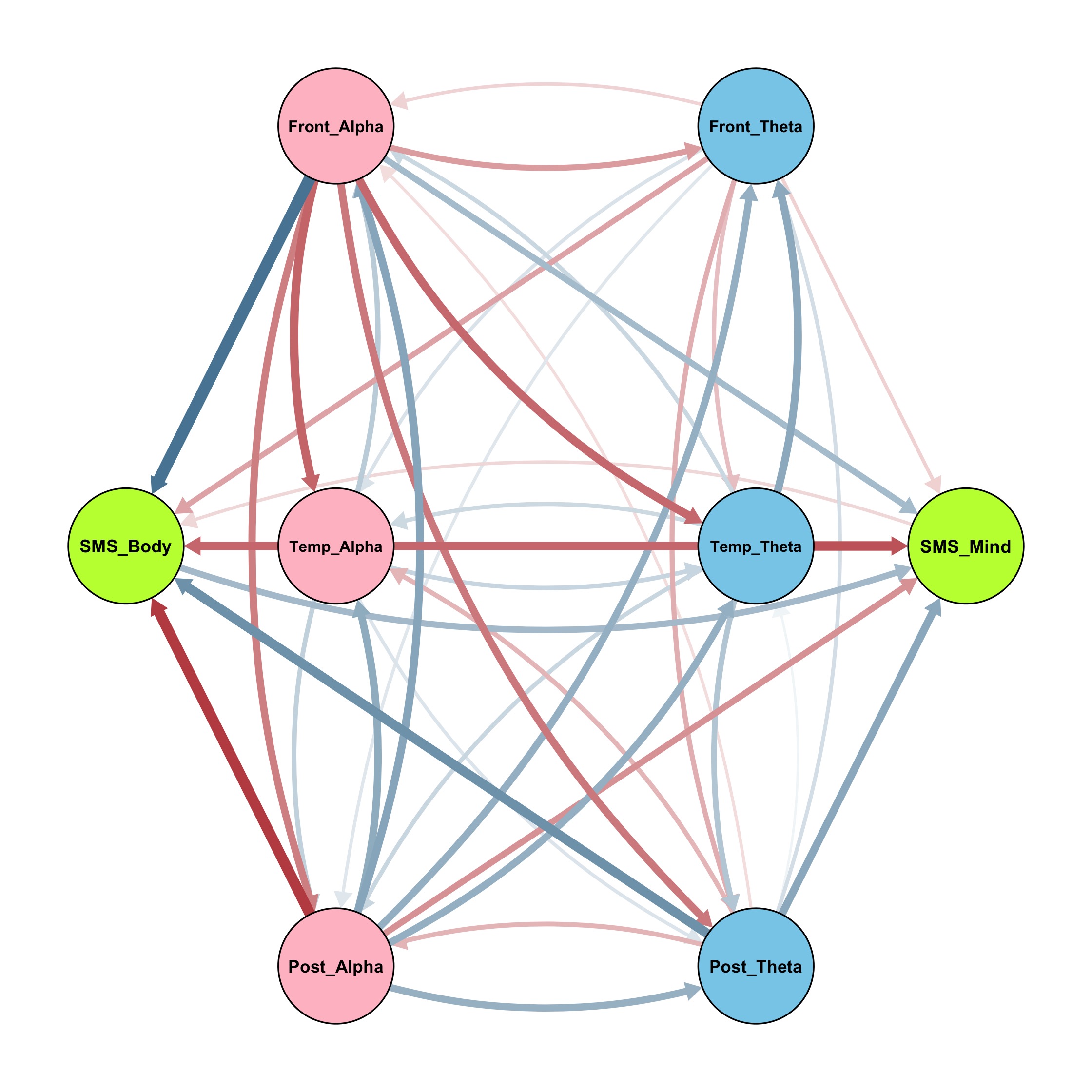

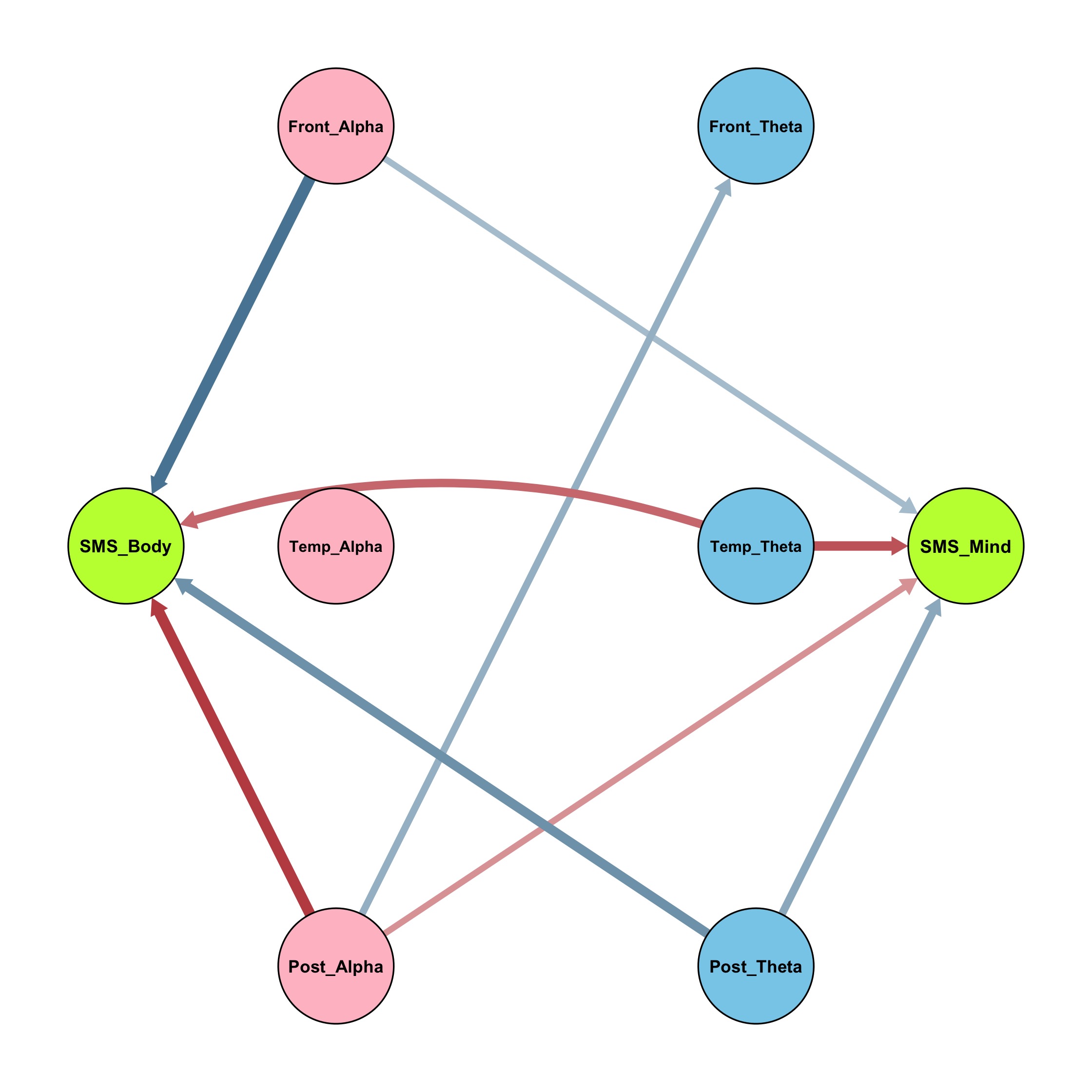

Results: regularization

Unregularized psychological network

Regularized psychological network

Alpha power; Theta power; Self-report mindfulness

Discussion

Brain is dynamical

- e.g., Posterior alpha can enhance frontal theta over time

Brain region (topography) matters

e.g., Frontal alpha power enhances mindfulness, while posterior alpha power suppresses mindfulness of body and mind over time.

e.g., Posterior theta power enhances mindfulness, while temporal-central theta power suppresses mindfulness

Identify ideal brain states

- e.g., According to centrality measures, frontal alpha and posterior theta are most important EEG signal for FA meditation training.

Conclusion

In neuroscience, psychological network could be very useful to understand brain activity patterns and their relationships with external behaviours.

But, you may wonder if it can be used to analyze the complex mental disorders?

4 Case Study 2: Gender Differences for Eating Disorder Symptom Networks

Research background

The present study examined sex-specific, symptom-level relationships among emotion regulation (ER), interpersonal problems (IP), and eating disorder (ED) psychopathology in a large sample of Chinese adolescents (Zhang et al., 2024).

Background: Eating disorders are serious issues for college students. The eating disorders symptoms are dangerous and co-occur with other psychological issues.

Motivation: Given the complex relationships between eating disorders with other risky behaviors, we need a novel model to untangle those interplay which can help with further intervention.

Assumption: Eating disorders combined with other risky factors be considered a network?

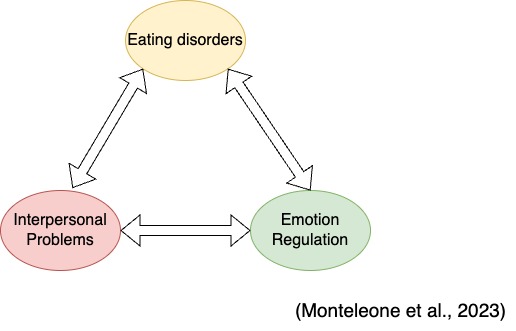

Eating Disorder Network?

Interrelationships among components—emotion regulation, interpersonal problems, and eating disorders:

Emotion regulation theory suggests that difficulties in emotion regulation can result in ED behaviors.

Interpersonal psychotherapy theory posits that interpersonal problems may exacerbate ED (Murphy et al., 2012).

Empirical studies consider these three to constitute an “ecosystem” (Ambwani et al., 2014). Emotion regulation and interpersonal functioning exhibit reciprocal effects on the maintenance of ED.

Advantages of longitudinal network

- It considers symptoms cause each other over time.

- It allows us to identify some symptoms may play the most important roles across time points

- It allows sex-specific developmental patterns of eating disorders

The motivation is to obtain a holistic picture of the eating disorders ecosystem. However, the symptom-level dynamics of eating disorders have not been well investigated.

Group Comparison and Research Questions

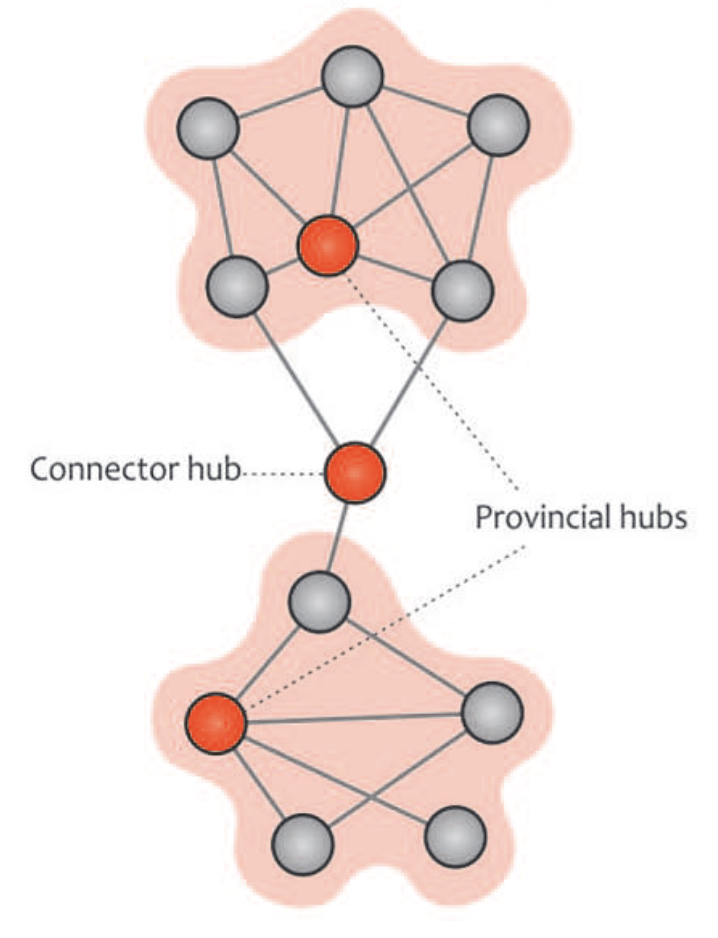

In network analysis, groups can be compared from three aspects:

Network structure (e.g., some nodes connected in group A but not in group B).

Node-level measures: node centrality (importance) or node bridging strength (e.g., some nodes may be more connected to other communities).

Network edge weights (e.g., node 1 and node 2 may have a strong relationship in group A but a weaker relationship in group B).

Research Questions:

Are there gender differences in the network structures of eating disorder longitudinal networks?

Are there gender differences in the network importance of longitudinal networks?

Are there gender differences in key paths of longitudinal networks?

Data & Measures

Sample

Four waves of data were collected over 18 months.

For each wave, demographic information and self-reports on three questionnaires (emotion regulation, interpersonal problems, and eating disorders) were collected from 1,652 high school students in China.

After data cleaning, N = 1,540 remained, including 53.9% girls and 46.1% boys.

Ages ranged from 11 to 17 years, with a mean of 15.2 years.

Measure

- Emotion regulation: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-18). Six subscales measure different aspects of emotion dysregulation: Awareness, Clarity, Goals, Non-acceptance, Impulse, Strategies.

- Interpersonal problems: Inventory of Interpersonal Problems—Short Circumplex (IIP-SC). Eight subscales measure varied aspects of interpersonal problems (e.g., domineering, cold, avoidant).

- Eating disorders: 12-item short form of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-QS). Twelve items measure different disordered eating behaviors.

We have 26 nodes in the initial networks.

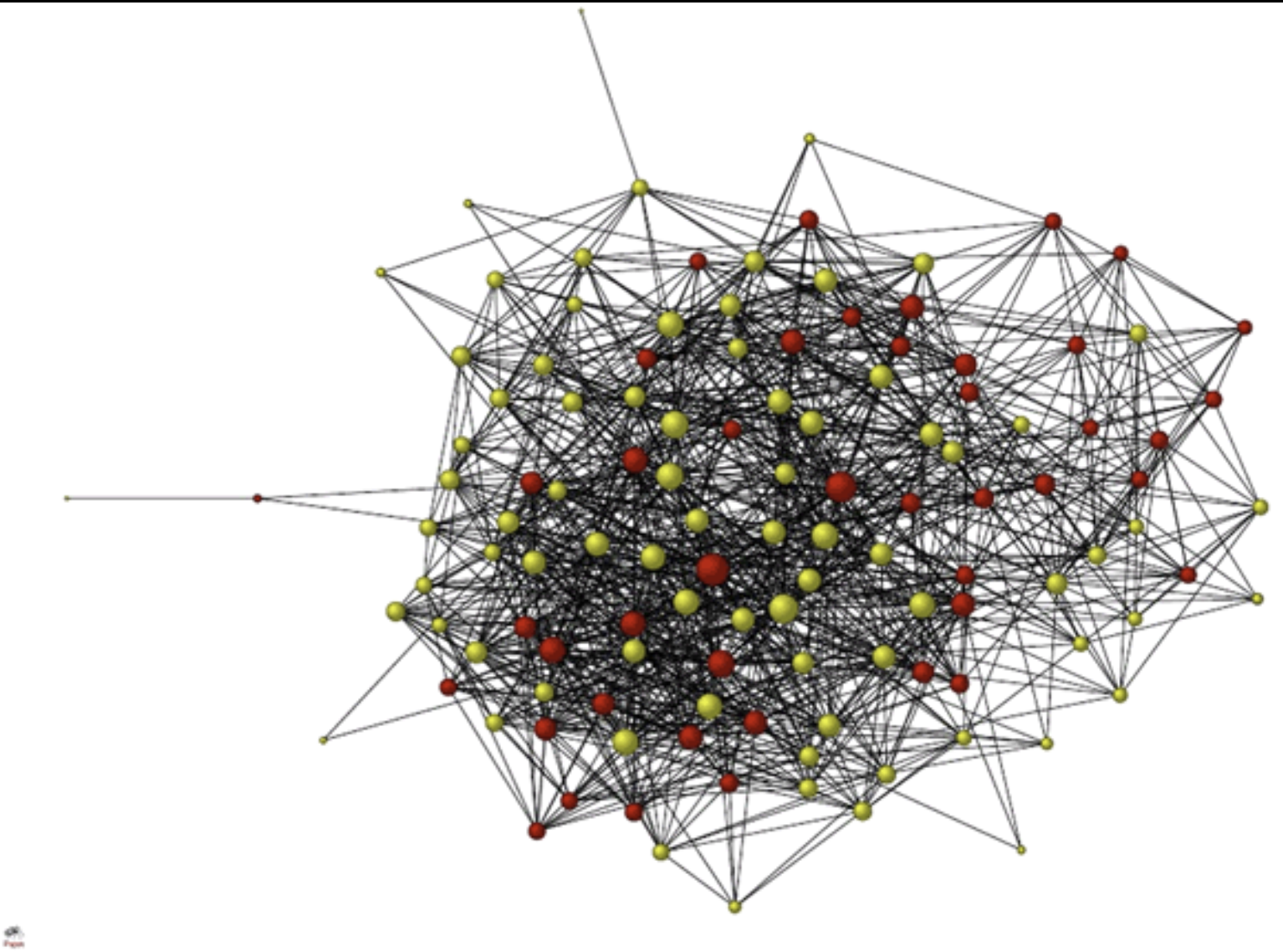

Results

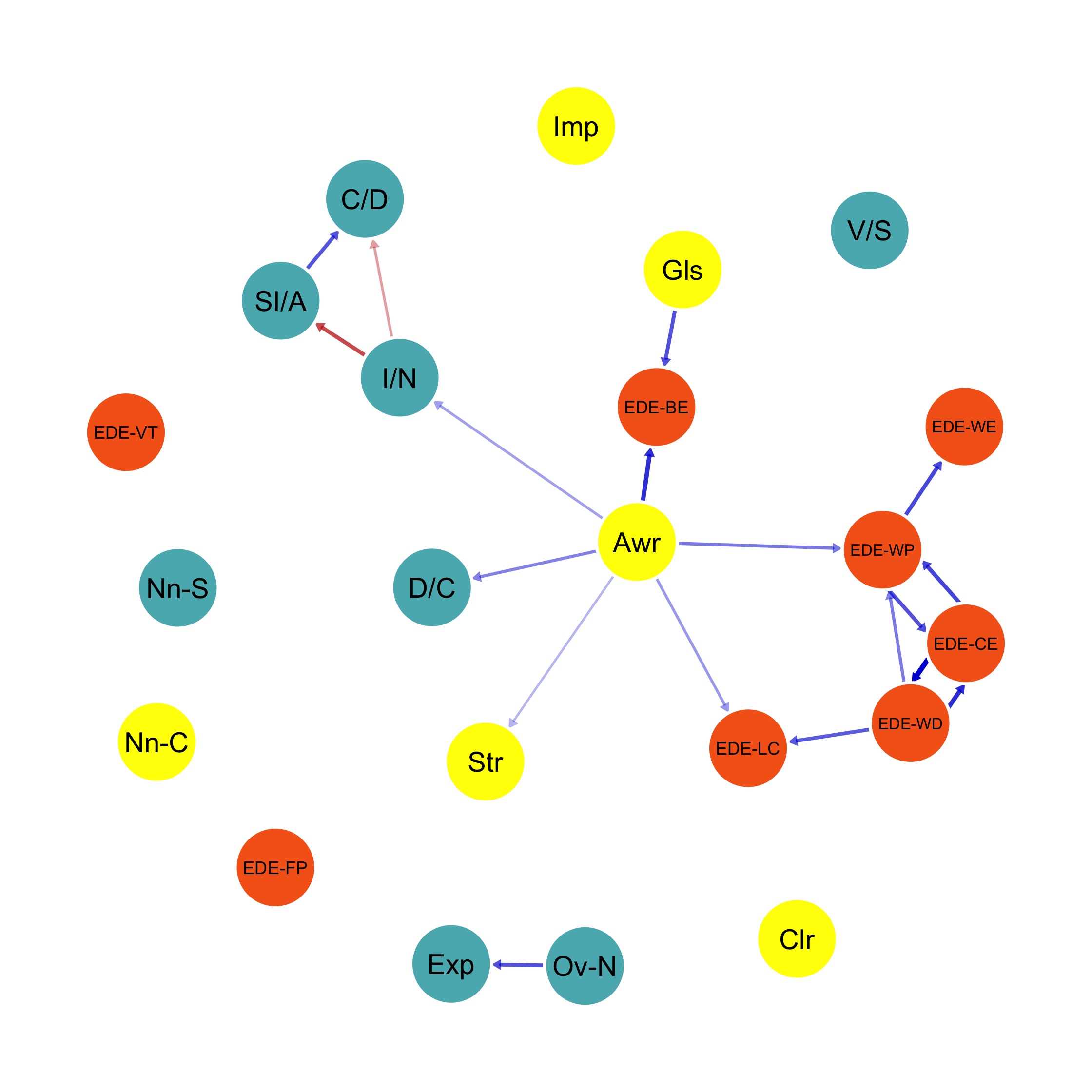

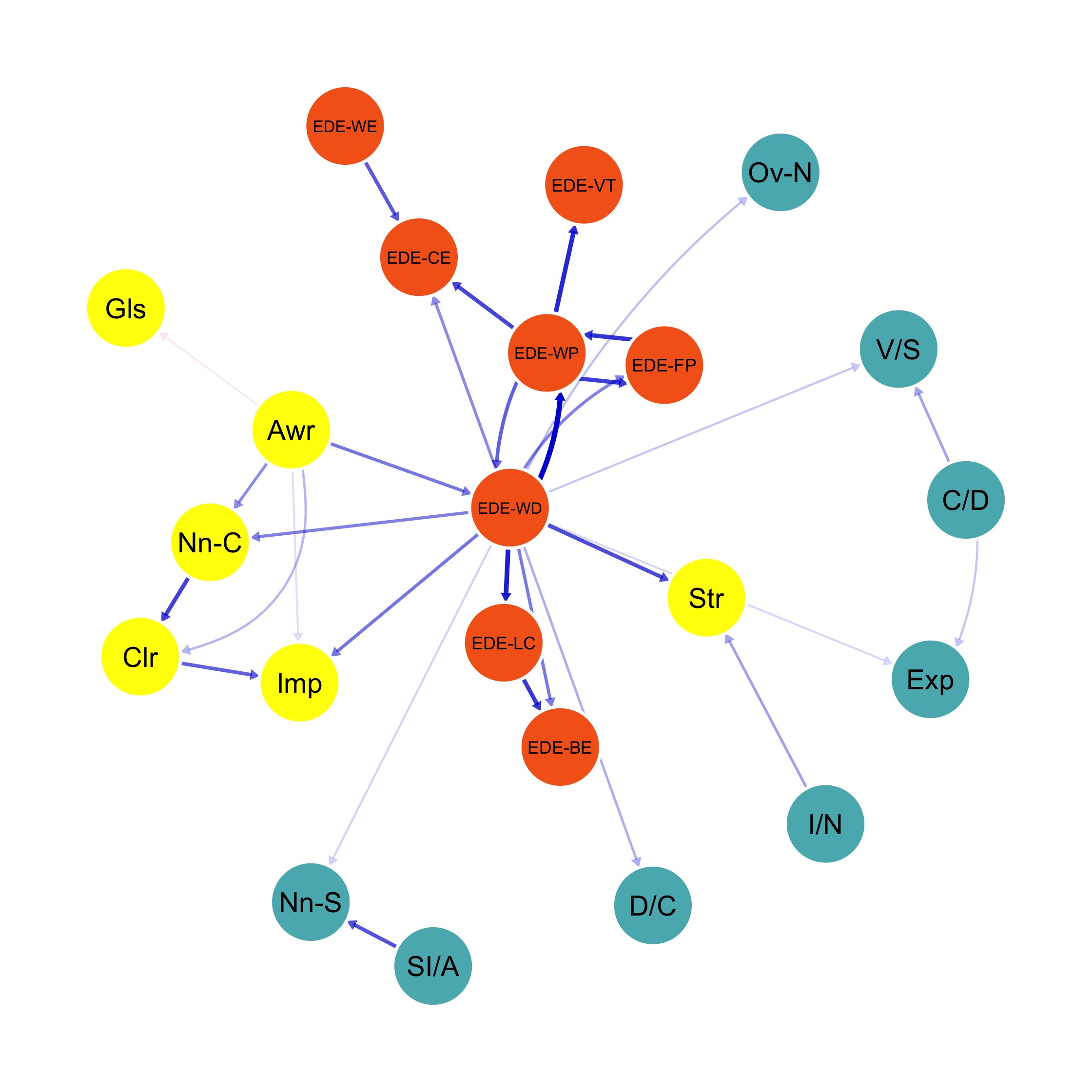

Temporal Network Structure (left: boys; right: girls)

Emotion Disorder; Interpersonal Problems; Eating Regulation

Overall Network Structure

Correlation Stability

- The multigroup network stability statistics were acceptable.

Boys

- Sparsity: 8.06% of non-zero edges (temporal)

- Strength: Mean (SD) of edge weights is 0.127 (0.094).

Girls

- Sparsity: 10.60% of non-zero edges (temporal)

- Strength: Mean (SD) of edge weights is 0.128 (0.102).

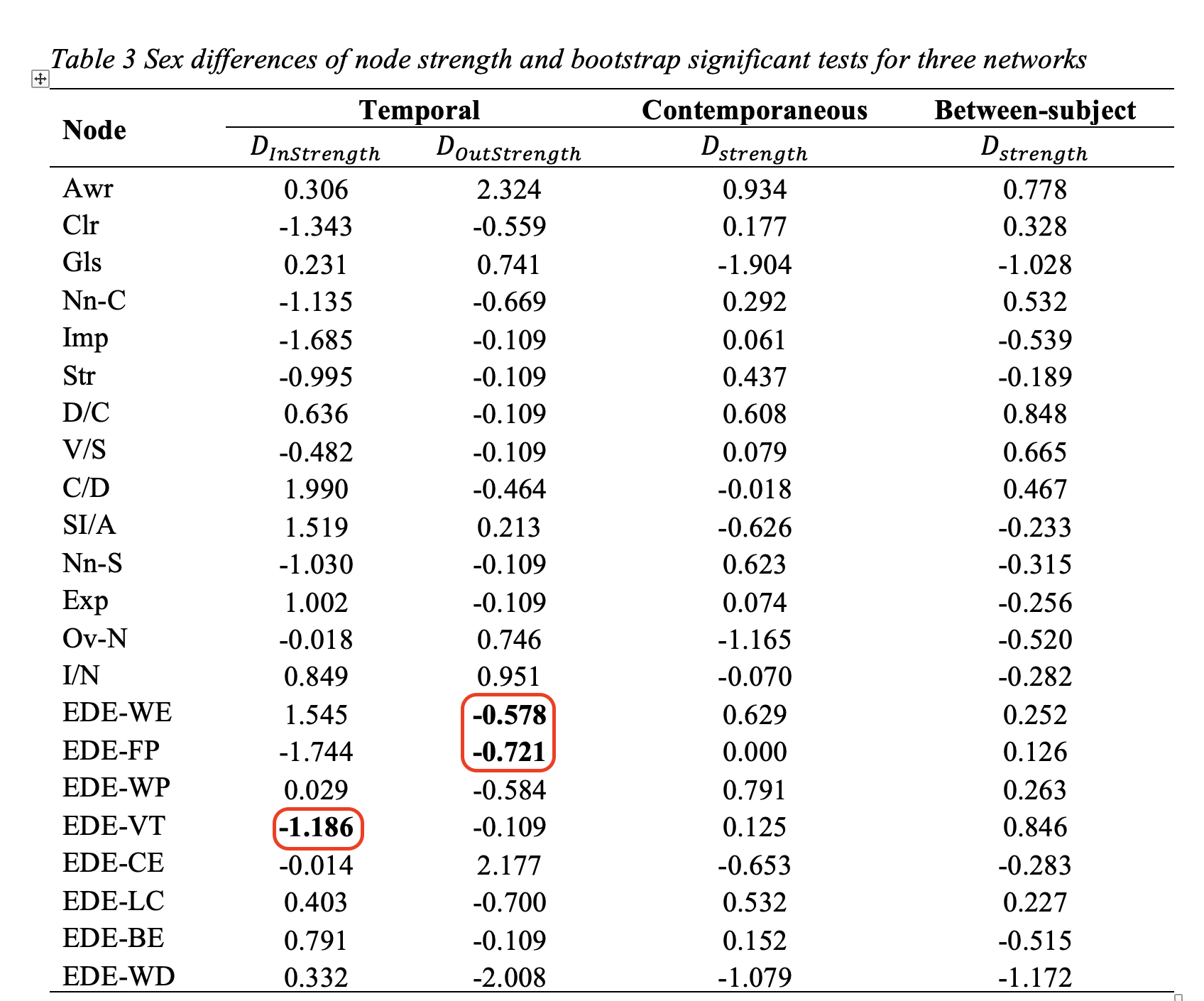

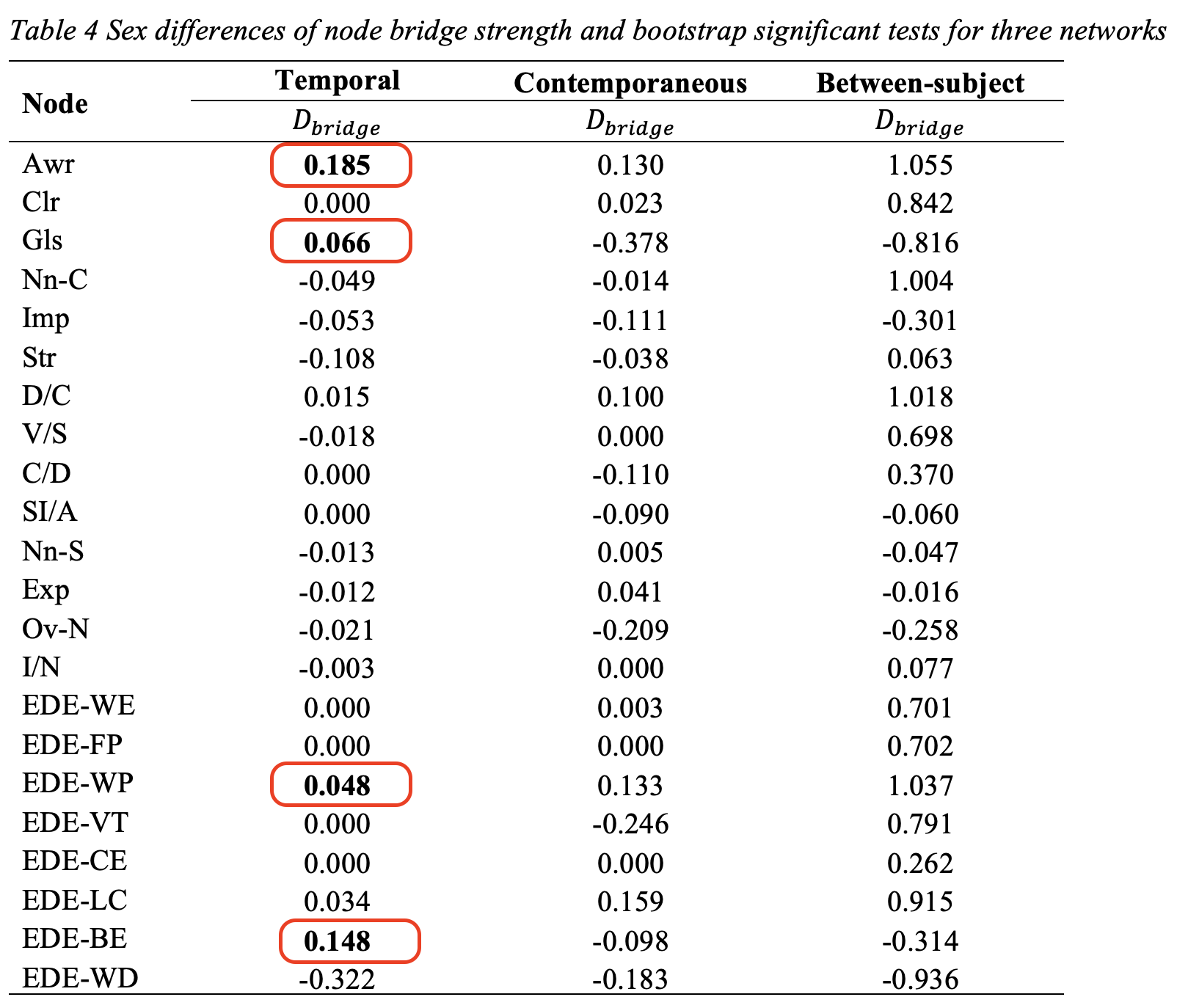

Network Hub (Important Symptoms) differences between sex groups

- Long periods without eating (EDE-WE) and Food preoccupation (EDE-FP) have significant sex differences in node out-strength.

- Weight/shape control by vomiting or taking laxatives (EDE-VT) has significant sex differences in node in-strength.

Network conncetor (Bridge Symptoms) differences between sex groups

- Awareness (Awr) and Goals (Gls) have significant sex differences.

- Weight/shape preoccupation (EDE-WP) and Binge eating episode (EDE-BE) have significant sex differences.

Target nodes for intervention on comorbidity.

Discussion

Group Commonalities

- Emotion dysregulation has consistent interconnections with eating disorders and interpersonal problems across genders.

Group Differences

- Overall network structures of boys and girls are significantly different.

- Overall, for boys, the most important bridging nodes were awareness and nonacceptance of the DERS, while weight/shape preoccupation and domineering/controlling emerged as the most central nodes.

- For girls, weight/shape dissatisfaction was identified as the most central symptom and the strongest bridging node.

Conclusion

Network psychometrics seems very promising to understand complex psychological phenomenon.

Is there any other novel psychometric areas? My answer is AI psychometrics.

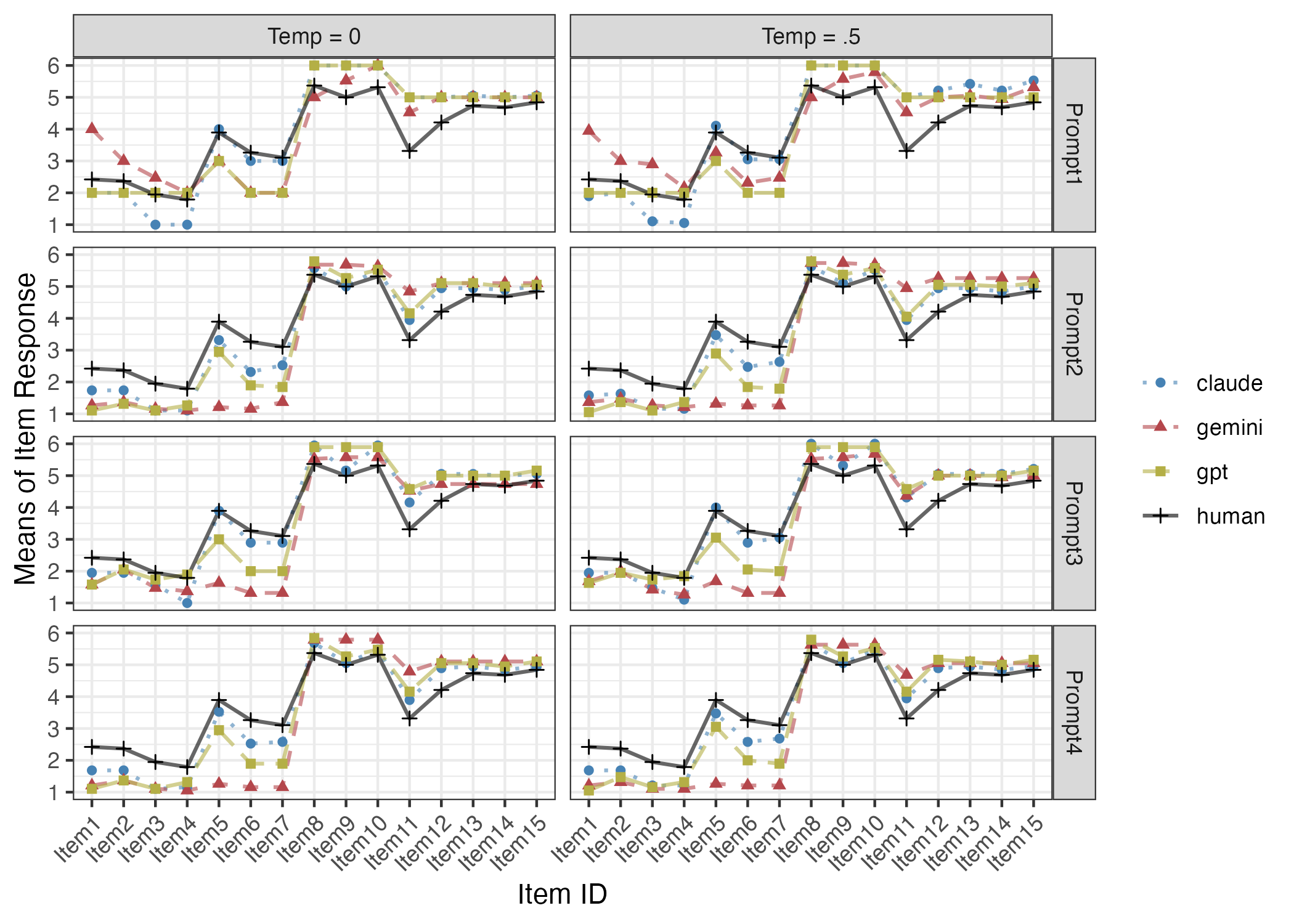

5 Further studies: AI psychometrics

AI-enhanced psychometrics is becoming more and more important.

AI data augmentation for test development

One of my recent project let AI participants can serve as the data points in psychometric assessment given enough accurate human information.

Interview-informed large language models can align with real human responses regarding survey responses very well.

Wrap-up

We talk about the network analysis framework

Two case studies showing how network analysis can be applied to different research areas

In the future, we need novel AI-driven methodology in AI era because AI can serve as research tools or data collection tools.

6 Q&A

Thank you.

Let me know if you have any questions.

You can also contact me via jzhang@uark.edu

Reference