Class Outline

- Brief intro to different types of experimental design

- Validity

- In-class AI quiz

1.1 Types of Experimental Design

There are three basic types of experimental research designs:

Pre-experimental designs: no control group

True experimental designs: control group, random assignment

Quasi-experimental designs: control group, but no random assignment. Assignment is often based on pre-existing criteria.

- e.g., Group A: high-performance vs. Group B: low-performance

A true experimental design also has different subtypes.

Characterized by the methods of random assignment and random selection.

These designs help control for extraneous variables.

1.2 Subtypes of true experimental designs

1.2.1 1. Post-test Only Design

- Features: control vs. treatment, randomly assigned

| Group | Treatment | Post-test |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | X | O |

| 2 | O |

1.2.2 2. Pre-Post-test Only Design**:

- Features: control vs. treatment, randomly assigned

A researcher wants to determine if a new reading intervention program improves reading comprehension in second-grade students.

- Group 1 (Treatment Group): Students are given a pre-test to assess their initial reading comprehension. They then participate in the new reading program for six weeks. After the program, they are given a post-test.

- Group 2 (Control Group): Students are also given the same pre-test. However, they continue with their standard reading curriculum. After six weeks, they are given the same post-test.

By comparing the pre-test and post-test scores between the two groups, the researcher can determine if the intervention program caused a significant improvement in reading comprehension compared to the standard curriculum.

1.2.3 3. Solomon Four-Group Design:

- Features: two treatment groups and two control groups. Only two groups are pre-tested.

- One pre-tested group and one un-pretested group receive the treatment.

- All four groups will receive the post-test.

- Use this design when it is suspected that taking a test more than once may cause earlier tests to affect later tests.

- The design is a combination of the pretest-posttest and posttest-only designs. It allows the researcher to control for the potential effects of a pre-test. The effect of the pre-test is known as a “testing threat” to internal validity. That is, the pre-test itself might influence the outcome.

- By using four groups, researchers can isolate the effect of the treatment from the effect of the pre-test and any interaction between the two. It helps to increase the external validity of the findings.

Imagine a study evaluating the effectiveness of a new diversity and inclusion training program in a company. Researchers are concerned that a pre-test measuring employees’ attitudes might make them more aware of the issues and thus influence their responses on the post-test, regardless of the training’s quality.

- Group 1 (Pre-test, Training, Post-test): Measures the effect of the training on employees who were sensitized by the pre-test.

- Group 2 (No Pre-test, Training, Post-test): Measures the effect of the training without pre-test sensitization.

- Group 3 (Pre-test, No Training, Post-test): Measures the effect of the pre-test itself. Did just taking the survey change their attitudes?

- Group 4 (No Pre-test, No Training, Post-test): Acts as the baseline control group.

By comparing the post-test results across these four groups, the researchers can determine the true effect of the training program, the effect of being pre-tested, and whether the pre-test made employees more or less receptive to the training.

| Group | Treatment | Pre-test | Post-test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X | O | O |

| 2 | X | O | |

| 3 | O | O | |

| 4 | O |

1.2.4 4. Factorial Design

The researcher manipulates two or more independent variables (factors) simultaneously to observe their effects on the dependent variable.

Features:

- It involves two or more independent variables (or factors).

- Each factor has two or more levels (conditions).

- It allows researchers to examine the main effects of each factor independently.

- Crucially, it also allows for the examination of interaction effects between factors, meaning the effect of one factor may depend on the level of another.

- This design allows for the testing of two or more hypotheses in a single project.

An investigation into the factors that cause stress in the workplace seeks to discover the effect of various combinations of background noise and interruptions on employee stress levels.

- Factor 1 (Independent Variable): Background Noise, with three levels (Low, Medium, High).

- Factor 2 (Independent Variable): Interruption Rate, with two levels (Low, High).

- Dependent Variable: Stress, measured by scores on a standardized stress test.

This is a 3x2 factorial design, which creates 3 * 2 = 6 different experimental conditions or groups:

- Low Noise / Low Interruptions

- Low Noise / High Interruptions

- Medium Noise / Low Interruptions

- Medium Noise / High Interruptions

- High Noise / Low Interruptions

- High Noise / High Interruptions

Participants would be randomly assigned to one of these six conditions. This design allows researchers to answer three key questions: - What is the main effect of background noise on stress? (i.e., does noise level, in general, affect stress?) - What is the main effect of interruptions on stress? (i.e., does the interruption rate, in general, affect stress?) - What is the interaction effect between noise and interruptions? (i.e., does the effect of interruptions on stress depend on the level of background noise? For example, perhaps high interruptions are only stressful when combined with high noise.)

1.2.5 5. Randomized Block Design

A technique for dealing with nuisance factors (variables that are not of primary interest but may influence the variables of interest).

Features: - Purpose: To minimize the effect of a single, known nuisance variable on the outcome. - Blocking: Participants are first divided into homogeneous groups or “blocks” based on the nuisance variable (e.g., age, gender, IQ). - Randomization: Within each block, participants are randomly assigned to the treatment or control conditions. - Benefit: This design reduces the variability of the data within each block, making it easier to detect the true effect of the treatment.

- Assume that we want to conduct a post-test-only design and recognize that our sample has several homogeneous subgroups.

In a study of college students, we might expect that students are relatively homogeneous with respect to class or year.

- We can block the sample into four groups: freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior.

- We will probably get more powerful estimates of the treatment effect within each block.

- Within each of our four blocks, we would implement the simple post-test-only randomized experiment.

| Block | Group | Treatment | Post-test |

|---|---|---|---|

| F. | 1 | X | O |

| F. | 2 | O | |

| Sop. | 1 | X | O |

| Sop. | 2 | O | |

| Ju. | 1 | X | O |

| Ju. | 2 | O | |

| Sen. | 1 | X | O |

| Sen. | 2 | O |

1.2.6 6. Repeated Measures Design

- Each group member in an experiment is tested for multiple conditions over time or under different conditions.

- An ordinary repeated measures design is one where patients are assigned a single treatment, and the results are measured over time (e.g., at 1, 4, and 8 weeks).

- A crossover design is where patients are assigned all treatments, and the results are measured over time.

- The most common crossover design is “two-period, two-treatment.” Participants are randomly assigned to receive either A and then B, or B and then A.

A study aims to test the effectiveness of a new medication for lowering blood pressure. Instead of using different groups for treatment and control, researchers recruit one group of patients.

- Baseline: The blood pressure of each patient is measured before the treatment begins.

- Treatment: All patients take the new medication for 30 days.

- Follow-up: Their blood pressure is measured again at 15 days and 30 days into the treatment.

Because the same participants are measured at multiple points in time, this is a repeated measures design. The key advantage is that it controls for individual differences between participants, making it a very powerful way to detect the effect of the treatment.

2 Validity

2.1 Why it matters

When we review experiments with a critical view, one question to ask is “is this study valid?”

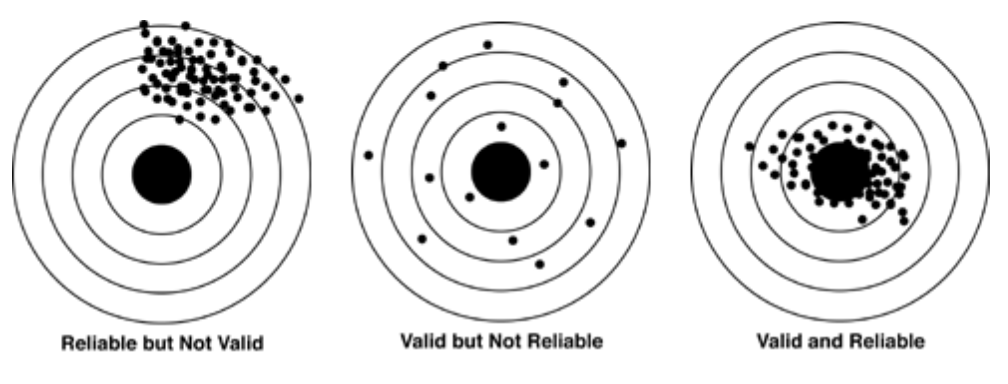

Validity is the foundation of trustworthy research. It ensures that the conclusions we draw are accurate and meaningful. Without it, we might be measuring the wrong thing, mistaking correlation for causation, or finding results that don’t apply to the real world.

- Internal Validity: Imagine a study finds that a new teaching method improves test scores. But what if the study took place over a whole year? The students might have improved simply because they got older and more mature, not because of the new method. If so, the study lacks internal validity.

- External Validity: A study finds that a new productivity app works great for a group of college students. But would it work for retired adults? Or for doctors in a busy hospital? If the results don’t generalize to other groups and settings, the study lacks external validity.

- Construct Validity: A researcher creates a survey to measure “happiness.” But if the questions are all about how much money someone makes, is it really measuring happiness, or is it measuring wealth? If the tool doesn’t accurately measure the theoretical concept, the study lacks construct validity.

2.2 Conceptions of Validity

- What is Validity? At its core, validity refers to the approximate truth and accuracy of the inferences or conclusions drawn from a study. It’s a judgment about how well the evidence supports the claims being made.

- Importantly, validity is never absolute; it’s a matter of degree. We talk about “strong” or “weak” validity, not “perfect” validity.

- Validity is About Inferences, Not Methods: This is a crucial distinction.

- A research method (like a survey or an experiment) is just a tool. The validity lies in how that tool is used and how the results are interpreted.

- Think of it like this: Owning a professional-grade oven (a strong research design) doesn’t guarantee a perfect cake (a valid conclusion). If you use the wrong ingredients or misread the recipe (poor implementation or analysis), the conclusion can be invalid.

- Therefore, simply using a powerful design does not guarantee a valid inference.

- No Design is Immune to Threats: Even the “gold standard” of research, the randomized experiment, cannot guarantee a valid causal inference on its own. It can be undermined or “broken” by issues such as:

2.3 Randomized Experiments

Randomized experiments are often called the “gold standard” of research design, particularly for establishing internal validity. The primary reason is that they are the most effective way to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between a treatment (cause) and an outcome (effect).

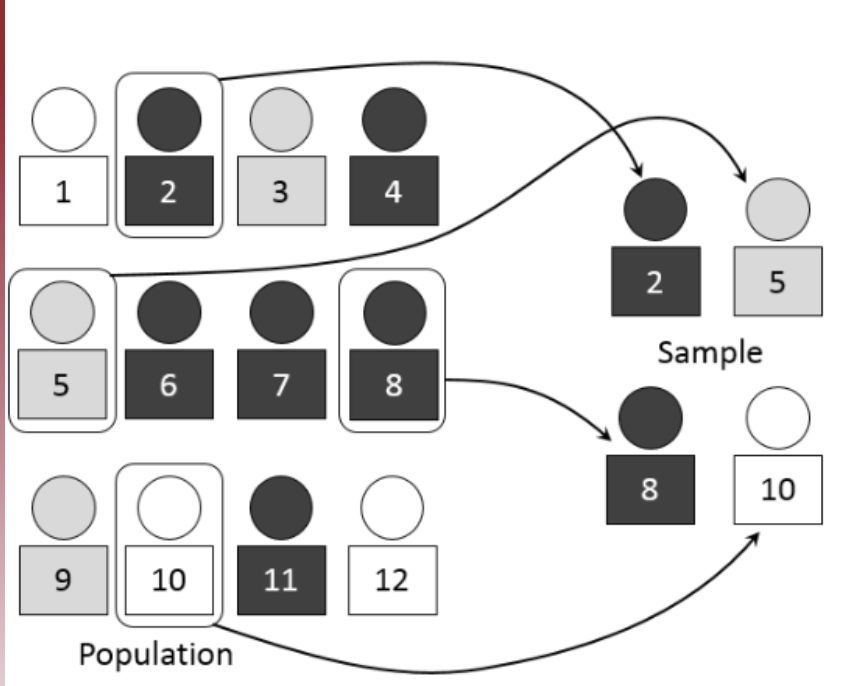

By randomly assigning participants to groups, the experimenter creates two or more groups that are statistically equivalent, on average, before the treatment is applied. This process minimizes selection bias and ensures that other potential causes (e.g., age, motivation, prior knowledge) are distributed equally across the groups.

Therefore, if a difference is observed between the groups after the treatment, the researcher can be much more confident that the difference was caused by the treatment and not by some other pre-existing factor.

Randomized experiments allow researchers to scientifically measure the impact of an intervention on a particular outcome of interest (e.g., the effect of intervention methods on performance).

The key to a randomized experimental research design is the random assignment of study subjects:

- For example, randomly assign individual people, classrooms, or some other group into a) treatment or b) control groups.

Randomization has a very specific meaning:

- It does not refer to haphazardly or casually choosing some and not others.

Randomization in this context means that care is taken to ensure that no pattern exists between the assignment of subjects into groups and any characteristics of those subjects.

- Ex: Not all females over 30 are in the exercise group, females 18-30 in the diet group, and males in the control group.

- Every subject is as likely as any other to be assigned to the treatment (or control) group.

2.3.1 Why Randomized Assignment

- Researchers demand randomization for several reasons:

- First, participants in various groups should not differ in any systematic way.

- In an experiment, if treatment groups are systematically different, the trial results will be biased.

- Suppose that participants are assigned to control and treatment groups in a study examining the efficacy of a walking intervention. If a greater proportion of older adults is assigned to the treatment group, then the outcome of the walking intervention may be influenced by this imbalance.

- The effects of the treatment would be indistinguishable from the influence of the imbalance of covariates (e.g., age), thereby requiring the researcher to control for the covariates in the analysis to obtain an unbiased result.

- In an experiment, if treatment groups are systematically different, the trial results will be biased.

2.3.2 Why Randomized Assignment (Cont.)

- Second, proper randomization ensures no a priori knowledge of group assignment.

- That is, researchers, participants, and others should not know to which group the participant will be assigned.

- Knowledge of group assignment creates a layer of potential selection bias that may taint the data.

- Trials with inadequate or unclear randomization tended to overestimate treatment effects up to 40% compared with those that used proper randomization!

- The outcome of the trial can also be negatively influenced by this inadequate randomization.

- That is, researchers, participants, and others should not know to which group the participant will be assigned.

2.4 Types of Validity

- Statistical Validity

- Internal Validity

- Construct Validity

- External Validity

2.5 1. Statistical Validity

- Statistical (Conclusion) Validity

- Question: “Was the original statistical inference correct?”

- There are many different types of inferential statistics tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression, correlation), and statistical validity concerns the use of the proper type of test to analyze the data.

- Did the investigators arrive at the correct conclusion regarding whether a relationship exists between the variables or the extent of that relationship?

- It is not concerned with the causal relationship between variables.

- It is concerned with whether there is any relationship, causal or not.

2.5.1 Statistical Validity (Cont.)

Concern:

- The primary concern is using the appropriate statistical tests to analyze the data.

Threats:

- Liberal biases: Researchers are overly optimistic about the existence of a relationship or exaggerate its strength.

- Conservative biases: Researchers are overly pessimistic about the absence of a relationship or underestimate its strength.

- Low power: The probability that the evaluation will result in a Type II error.

Causes of Threats:

- Small sample sizes, violation of statistical assumptions, too many repeated experimental trials, use of biased estimates of effects, increased error from irrelevant, unreliable, or poorly constructed measures, high variability due to participant diversity, etc.

2.5.2 Addressing Threats to Statistical Validity

- Different statistical inference methods have different tools to address validity:

- Effect size

- p-value adjustments for multiple comparisons

- Controlling for Type I error

- Including control variables (e.g., gender, race, age)

- Power analysis (to ensure an appropriate number of participants are recruited and tested)

2.6 2. Internal Validity

- Internal Validity:

- Question: “Is there a causal relationship between variable X and variable Y, regardless of what X and Y are theoretically supposed to represent?”

- Internal validity occurs when it can be concluded that there is a causal relationship between the variables being studied.

- A danger is that changes might be caused by other factors.

- Threats to internal validity:

- Maturation, history, instrumentation, regression, selection, etc.

- Diffusion or imitation of treatments, compensatory equalization of treatments, compensatory rivalry by people receiving less desirable treatments (John Henry effect), and resentful demoralization of respondents receiving less desirable treatments.

Imagine a study measures the effectiveness of a 3-month public health campaign designed to increase recycling.

- Pre-test: Researchers measure recycling rates in a city.

- Treatment: The public health campaign runs for 3 months.

- Post-test: Researchers measure recycling rates again and find a significant increase.

The conclusion seems to be that the campaign worked. However, during that same 3-month period, a very popular celebrity independently launched their own high-profile “Go Green” initiative. Now, it’s impossible to know if the increase in recycling was due to the health campaign or the celebrity’s influence. This external event is a history threat that compromises the study’s internal validity.

2.7 3. External Validity

- External Validity

- Question: “Can the finding be generalized across populations, settings, or time?”

- A primary concern is the heterogeneity and representativeness of the evaluation sample population.

- e.g., In many psychology experiments, the participants are all undergraduate students and come to a classroom or laboratory to fill out a series of paper-and-pencil questionnaires or to perform a carefully designed computerized task.

Consider, for example, an experiment in which researcher Barbara Fredrickson and her colleagues had undergraduate students come to a laboratory on campus and complete a math test while wearing a swimsuit (Fredrickson et al., 1998). At first, this manipulation might seem silly. When will undergraduate students ever have to complete math tests in their swimsuits outside of this experiment?

Assumption: “This self-objectification is hypothesized to (a) produce body shame, which in turn leads to restrained eating, and (b) consume attention resources, which is manifested in diminished mental performance.”

“Self-objectification increased body shame, which in turn predicted restrained eating.”

In one such experiment, Robert Cialdini and his colleagues studied whether hotel guests chose to reuse their towels for a second day as opposed to having them washed as a way of conserving water and energy (Cialdini, 2005).

- These researchers manipulated the message on a card left in a large sample of hotel rooms.

- One version of the message emphasized showing respect for the environment.

- Another emphasized that the hotel would donate a portion of their savings to an environmental cause.

- A third emphasized that most hotel guests choose to reuse their towels.

- Results: Guests who received the message that “most hotel guests choose to reuse their towels (Message 3)” reused their own towels substantially more often than guests receiving either of the other two messages.

- Guests were randomly selected, hotels were randomly chosen, and a large sample of hotel rooms was used.

Threats to External Validity:

- Interaction of Selection and Treatment: Does the program’s impact apply only to this particular group, or is it also applicable to other individuals with different characteristics?

- Interaction of Testing and Treatment: If your design included a pre-test, would your results be the same if implemented without one?

- Interaction of Setting and Treatment: How much are your results impacted by the program’s setting, and could you apply this program within a different setting and see similar results?

- Interaction of History and Treatment: A simplified way to think about this is to ask how “timeless” the program is. Could you get the same results today in a future setting, or did something specific to this time point (e.g., a major event) influence the impact?

- Multiple Treatment Threats: The program may exist in an ecosystem that includes other programs. Can the results be generalized to other settings without the same program-filled environment?

As a general rule, studies are higher in external validity when the participants and the situation studied are similar to those that the researchers want to generalize to and that participants encounter every day, often described as mundane realism.

The best approach to minimize this threat is to use a heterogeneous group of settings, people, and times.

2.8 4. Construct Validity

- This may be the “broadest” or most “vague” concept among the validity types.

- “Do your measured math scores represent MATH?”

- DEFINITION: The degree to which a test or instrument is capable of measuring a concept, trait, or other theoretical entity.

- “Do the theoretical constructs of cause and effect accurately represent the real-world situations they are intended to model?”

- It is the general case of translating any construct into an operationalization.

- For example, if a researcher develops a new questionnaire to evaluate respondents’ levels of aggression, the construct validity of the instrument would be the extent to which it actually assesses aggression as opposed to assertiveness, social dominance, and so forth.

- There are subtypes of construct validity:

- Convergent validity (=congruent validity): The extent to which responses on a test or instrument exhibit a strong relationship with responses on conceptually similar tests or instruments.

- Discriminant validity (=divergent validity): The degree to which a test or measure diverges from (i.e., does not correlate with) another measure whose underlying construct is conceptually unrelated to it.

- Face validity, content validity, predictive validity, concurrent validity, etc.

2.8.1 4. Construct Validity II

- Threats:

- Experimenter bias: The experimenter transfers expectations to the participants in a manner that affects performance on dependent variables.

- For instance, the researcher might look pleased when participants give a desired answer.

- If this is what causes the response, it would be wrong to label the response as a treatment effect.

- Condition diffusion: The possibility of communication between participants from different condition groups during the evaluation.

- Resentful demoralization: A group that is receiving nothing (control/placebo) finds out that a condition (treatment) that others are receiving is effective.

- Inadequate Preoperational Explication: Preoperational means before translating constructs into measures or treatments, and explication means explanation.

- The researcher did not do a good enough job of defining (operationally) what was meant by the construct.

- Mono-method bias: The use of only a single dependent variable to assess a construct may result in under-representing the construct and containing irrelevancies.

- Mono-operation bias: The use of only a single implementation of the independent variable, cause, program or treatment in your study.

- Experimenter bias: The experimenter transfers expectations to the participants in a manner that affects performance on dependent variables.

2.8.2 4. Construct Validity III

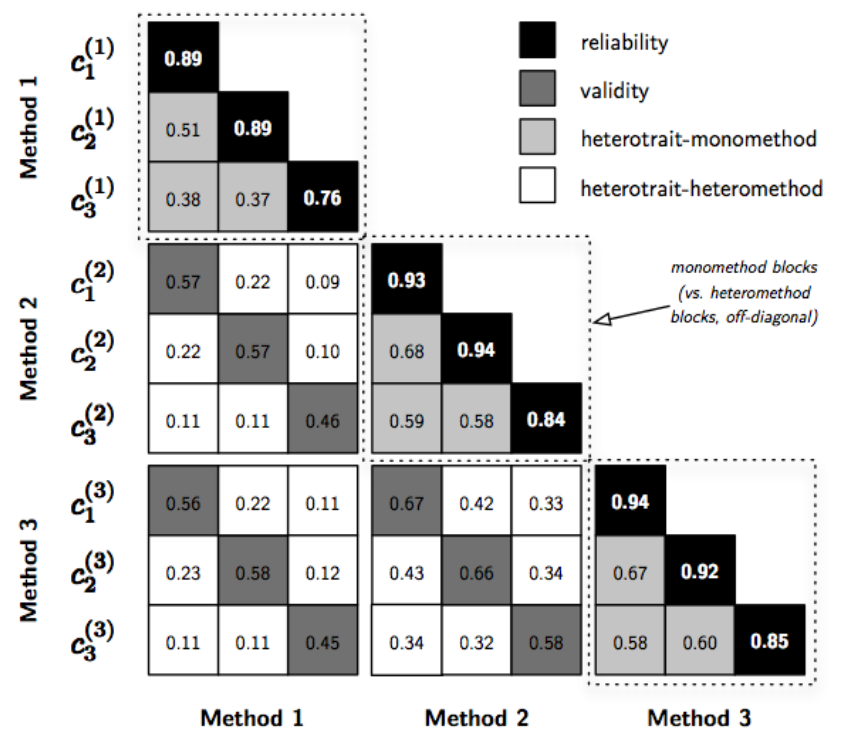

- Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix (MTMM):

- The MTMM is an approach to assessing the construct validity of a set of measures in a study (Campbell & Fiske, 1959).

- Along with the MTMM, Campbell and Fiske introduced two new types of validity, both of which the MTMM assesses:

- Convergent validity is the degree to which concepts that should be related theoretically are interrelated in reality.

- Discriminant validity is the degree to which concepts that should not be related theoretically are, in fact, not interrelated in reality.

- In order to be able to claim that your measures have construct validity, you have to demonstrate both convergence and discrimination.

2.8.3 4. Construct Validity IV

- Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix (MTMM):

- Example: Three traits to be measured: c1 (geometry), c2 (algebra), and c3 (reasoning).

- Each trait was measured by three methods.

- e.g., notation: c_3^{(2)} is trait 3 measured by method 2.

- Coefficients in the reliability diagonal should consistently be the highest in the matrix: a trait should be more highly correlated with itself than with anything else!

- Coefficients in the validity diagonals should be significantly different from zero and high enough to warrant further investigation.

- This is essentially used as evidence of convergent validity.

2.9 In-class Exercise

2.10 Wrap-up

- Choosing the Right Design: The selection of an experimental design—from a simple post-test to a complex factorial or repeated measures design—is crucial for effectively answering your research question. Each design has unique strengths for controlling different variables and threats.

- The Four Pillars of Validity: A well-designed experiment is not enough; its conclusions must be valid. Always consider the four key types of validity to ensure your findings are trustworthy:

- Statistical Validity: Are your statistical conclusions accurate?

- Internal Validity: Did your treatment truly cause the effect?

- Construct Validity: Are you measuring what you intend to measure?

- External Validity: Can your findings be generalized to other people, settings, and times?